Restoring Savana Island: A Haven for the Endangered Virgin Islands Tree Boa

A new home for an endangered snake is motivating collaboration in the Caribbean!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

November 27, 2023

Written by

Jesse Friedlander

Photo credit

Jesse Friedlander

By: Jesse Friedlander, South and West Pacific Project Manager / Island Conservation

Craning my neck to catch a glimpse of our destination, the beauty and fragility of Tuvalu’s Funafuti Atoll were very apparent from the air. Its 29 small islets are dwarfed by the huge lagoon, over 100 square miles in size. As we come in to land, my daydreaming is cut short. The engines of our small aircraft rev as we ascend again. The pilot’s voice came over the speaker, “My apologies, there is some wildlife on the runway.” ‘Wildlife,’ I found out later, meant semi-wild dogs and pigs, both of which congregate on the airstrip in large numbers.

This trip is my first to Tuvalu, and Island Conservation’s first foray into the Pacific nation, a country composed of three reef islands and six atolls situated halfway between Hawaii and Australia.

Our mission is to remove harmful invasive rats that are eating native species eggs and young from two small islets, thereby restoring seabird-driven ecosystems. This will help to ensure Tuvalu retains healthy inshore reefs, which are reliant on the nutrients delivered by healthy seabird populations.

For Tuvalu, having healthy inshore reef systems isn’t a ‘nice-to-have.’ Without strong reefs, the low atolls and islands of Tuvalu, which have a maximum elevation of only 4.6m, will be much more vulnerable to rising sea levels and increasingly frequent and severe cyclones and tropical storms. As we drive to our accommodation, we watch as diggers busily move sand around, piling it behind sandbags in a reclaimed area that was once part of the lagoon.

This is Tuvalu’s latest attempt to hold out against the rising tide.

After a few days meeting government ministers and assembling our team, we are keen to see the islets of Tepuka and Falefatu for ourselves. Our first view of Tepuka shows a typical paradisical setting, a diamond-shaped islet of 10 hectares with golden beaches and swaying palm trees, an image not unlike something you might have as your screensaver. As we get closer, however, we spot invasive rats at the high tide mark.

Rat abundance is certainly very high, and we will have our work cut out for us to restore this degraded ecosystem.

Our second shock comes as we enter the forest. Apart from the scurrying rats, things are peaceful for 10 seconds or so until we all become aware of a crawling sensation. We are being swarmed by Yellow Crazy Ants, a particularly nasty invasive species now present on many Pacific islands. Tepuka is seething with them, and the team is very happy to forego the option of camping on site in favor of the daily commute from Fongafale.

Our second stop is Falefatu. This small (6ha), thin islet is located on the Southern rim of the lagoon and has a house with two permanent residents at its Southern end. In preparation for our arrival, our hosts have penned up the pigs and ducks around their house to keep them safe. We explain to our hosts that we need to set traps for rats to take DNA samples—but they reveal that they’ve already trapped 12 rats around the house just last night. The rat population seems to be dangerously high here too!

Despite the presence of invasive rats, it was encouraging to see some Black Noddies, Brown Noddies, and White Terns still present and nesting in Pisonia trees nearby.

With all preparations and training of our hard-working local team complete, it was finally time to start the real work. To remove invasive rats from an island, we will have to cut and mark a 20x20m grid across both islets through the rats’ territory. There is a slight snag in this plan, however, as our equipment, planned to arrive months before, has not yet landed in Tuvalu. Forced to improvise, we empty every store in Tuvalu of decorative ribbon (to be used as a flagging tape replacement) and BBQ skewers (to be used as pin flags to monitor bait uptake). Luckily, the hardware store has a good stock of machetes.

Each day, the team assembles at the boat ramp on Fongafale, fueled up on samosas from the local bakery (with the obligatory samosa given to the well-fed bakery dog).

We commute to Tepuka and Falefatu on a small fishing boat. On the third day cutting the grid, I find myself hiking up a short rise covered with coconut trees. In my sweaty, tired state, it takes a while to realize that what I am standing on is not a natural land feature: it’s a very large, dilapidated WW2 bunker covered in coconut trees and fern. After a week battling thick pandanus, coastal scrub, and Yellow Crazy Ants, we emerge from the forest a little worse for wear but happy to have the hard part over.

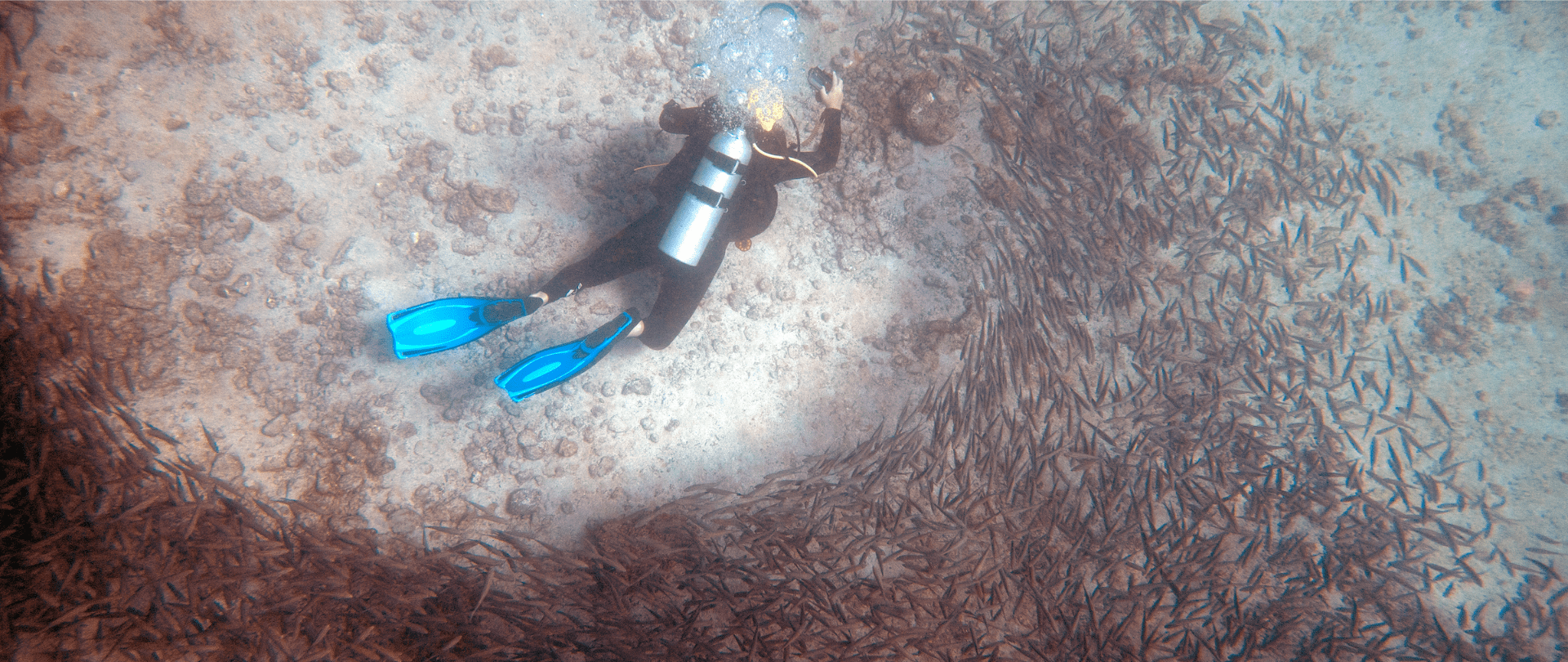

Baiting the islands is comparatively easy, and the two-week interval between applications gives us the opportunity to explore the rest of the atoll and confirm the rat-free status of Funafuti’s amazing conservation islets. The Funafuti Conservation Area covers 12.74 square miles of reef, lagoon, and motu (islets) on the western side of the atoll. The islets are nesting sites for the green sea turtle and hold large nesting populations of seabirds. Six islets are included in the Funafuti Conservation Area: Tepuka Vili Vili, Fualopa, Fuafatu, Vasafua, Fuagea, and Tefala.

Confirming the absence of invasive rats by setting traps on each of these islets almost seems like a waste of time, as it is obvious to us all that the ecosystems are in great health. White Terns and noddies take off in huge flocks as we approach each islet, while Greater Frigate Birds hang in the breeze, waiting for an easy meal.

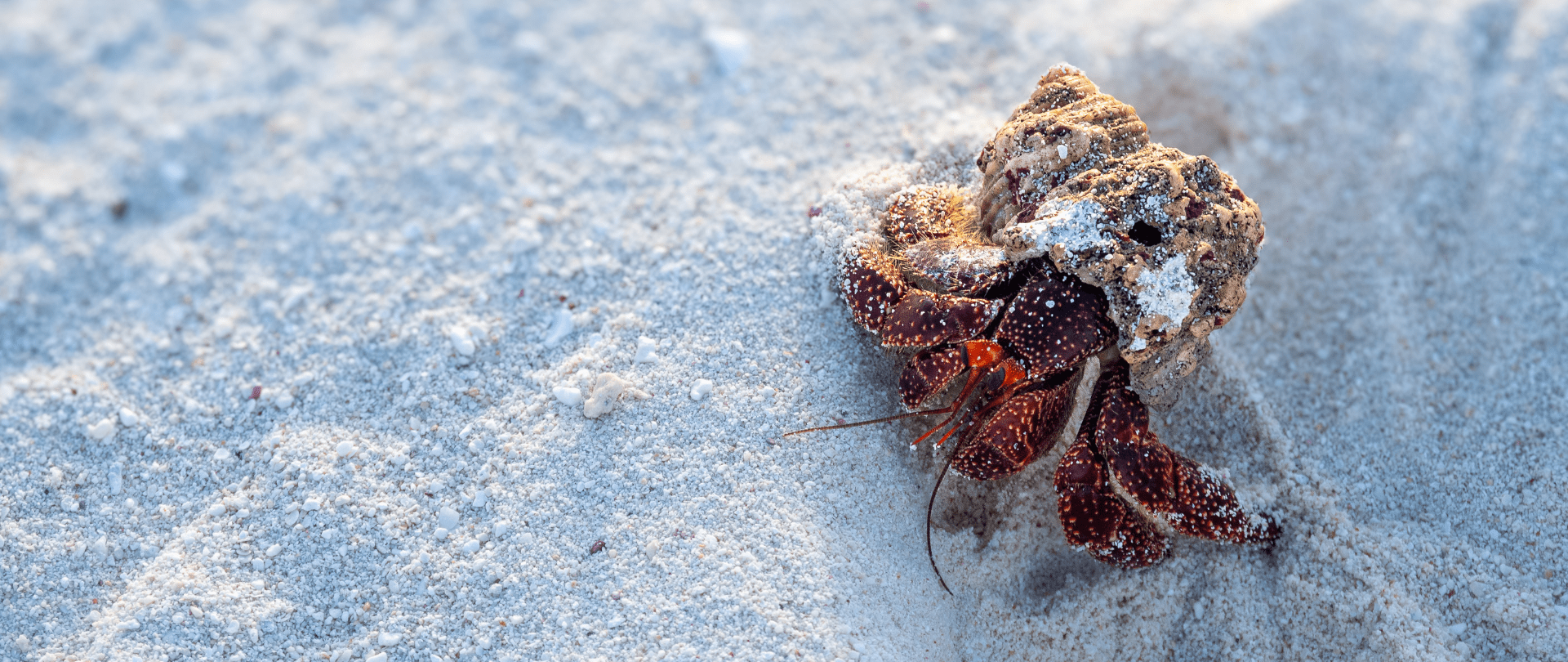

Once in the forest, we see Coconut Crabs in large numbers. In Tepuka and Falefatu, by contrast, the only Coconut Crabs we saw were dead—likely killed by Yellow Crazy Ants.

For me, visiting these pristine islets is the best part of the trip, as we get to see a real-life example of the impact our work removing invasive species from islands can have.

With the second bait application complete, and a deep craving for some fresh fruit and vegetables, it is time to bid our new friends farewell. We will be back in Tuvalu next year to assess and monitor these eradications and continue our work, this time on the outer islands and atolls.

Some may wonder why we would spend time and money on low islands and atolls on the frontlines of sea level rise, rather than focusing exclusively on high islands.

As my colleague Paul Jaques wrote in his recent article on the benefits of restoring atolls, “By restoring atoll ecosystems, we see renewed abundance of seabirds, land crabs, and turtles, species that join deep ocean, reef, and islets in the ongoing cycle of renewal that may keep coral atolls above the water for generations to come.”

By expanding our work to include inhabited islands and atolls in Tuvalu, we also hope to improve livelihoods and food security for human communities. Soils on coral atolls are of low quality, and Tuvalu’s atolls are no exception, with very few fresh fruits and vegetables available. We heard how invasive rats eat all the seeds from raised garden beds (used to reduce water usage and stop saltwater infiltrating from below), thereby further impacting food security for local people who are already vulnerable to climate change. By continuing to remove invasive species from atolls and islands of Tuvalu, we hope to be part of the solution to a threat to Tuvaluan people and biodiversity not of their making.

Jesse Friedlander is a Project Manager for Island Conservation. You can support Jesse’s work in Tuvalu and Island Conservation’s many projects around the world by becoming a donor today!

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

A new home for an endangered snake is motivating collaboration in the Caribbean!

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Mona Island, Puerto Rico is a key nesting ground for endangered species--but it's in danger! Read about our project to protect this beautiful, biodiverse island.

Read Coral Wolf's interview about the thrilling news of rare birds nesting on Kamaka

Audubon's Shearwaters are nesting on Desecheo Island for the first time ever! Read about how we used social attraction to bring them home.

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!

A recent monitoring trip to Late Island shows promising results!