The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

December 3, 2019

Written by

Emily Heber

Photo credit

Emily Heber

Invasive species are one of the leading threats to seabird colonies around the world–predating eggs, chicks, and adults while destroying native vegetation. Luckily, removing invasive species from islands is one of the most effective conservation actions available today and has been proven to restore islands and prevent the extinction of wildlife. Following restoration, many islands recover as if overnight, but seabird colonies that disappeared almost a century before sometimes require additional intervention including social attraction.

Island Conservation and our partners have begun implementing social attraction projects on islands now free of invasive species, in hopes of restoring thriving colonies that were lost due to invasive predators. Social attraction including the use of seabird calls and decoy seabirds encourages native birds to come to the island that is once again safe for nesting.

The removal of invasive species made Desecheo into a new Island: more seabirds and land birds are present and there is significant growth of new vegetation in areas where it was once mostly bare ground.”

Jose Luis Herrera

Desecheo Island was once a major nesting area for thousands of seabirds which blackened the sky above like a perpetual storm cloud. Introduced invasive species devastated the seabird population, but thanks to a groundbreaking restoration project in 2016, the birds are now returning to their native home.

Our team is bringing seabirds back to Desecheo using social attraction including Bridled Tern decoy colonies and recordings of Audubon’s Shearwater calls to attract these species to the island.

In 2019, we documented an Audubon’s Shearwater visiting the island on a nightly basis—an exciting result as this species had never before been recorded on Desecheo. The team also documented several Bridled Tern eggs in areas where nesting activity was not common in the past. Additionally, Brown Noddies, American Oystercatchers, Frigatebirds, and Brown Boobies are once again thriving.

After a second year of success Island COnservation’s Jose Luis can see his team’s efforts paying off: “Seabirds are returning to Desecheo and we’re hopeful that one day in the not too-distant future we’ll have an island full of activity.”

It has been incredible to see the population of Peruvian Diving-petrels increase on Choros since the removal of invasive rabbits, but I am even more excited that this resilient population will also help us to restore the population expelled from Chañaral Island.”

Maria Vilches

After the removal of invasive rabbits from Choros in 2013, Island Conservation’s Coral Wolf returned to study the recovery of Chile’s largest Peruvian Diving-petrel population.

The petrels are thriving. Coral’s team documented an estimated 50,000 breeding pairs—six times the number of pairs when invasive rabbits were present. The number of overall colonies has tripled and the growing population shows the dramatic effect that conservation interventions can have for seabirds on the brink.

In late 2019, Island Conservation’s Maria Vilches began restoring seabirds to nearby Chañaral Island, which was freed of invasive vertebrates in 2017. Chañaral was once home to a thriving petrel colony, but invasive vertebrate species put an end to that breeding population, and none breed there today.

Island Conservation has initiated a social attraction project using recorded petrel calls from Choros to help restore the population on Chañaral. Recolonization will help make this endangered species more resilient to future threats and further the recovery of the global population of Peruvian Diving-petrels.

Featured photo: Bridled Terns perched on the cliffs of Desecheo Island. Credit: Island Conservation

The restoration of Choros and Chanral Island was completed in partnership with Corporación Nacional Forestal and Universidad Católica del Norte. This project was made possible by funding from American Bird Conservancy and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

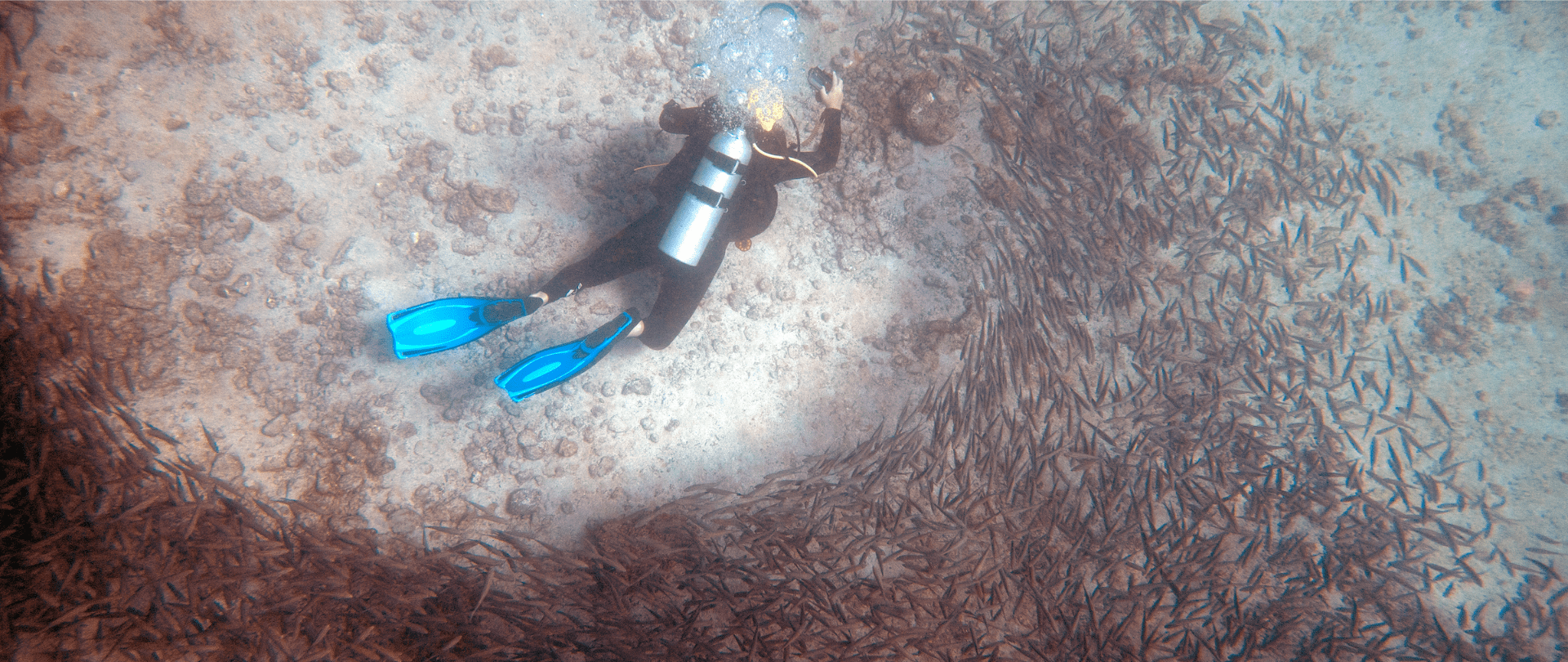

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!