April 9, 2025

Firman acuerdo para proteger al pingüino de Humboldt en isla Cachagua

La Municipalidad de Zapallar firmó un convenio con Island Conservation para proteger al pingüino de Humboldt y la biodiversidad de la Isla Cachagua.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Looking to make an impact this Earth Month? Here’s how.

Citizen scientist and Island Conservation Board Member Jim Torgerson journeyed to Kamaka Island in French Polynesia to help implement social attraction infrastructure for endangered Polynesian Storm-petrels. Read his inspiring account and learn about what Island Conservation is doing to accelerate recovery for delicate island ecosystems!

“The cockroaches running across your face at night can be a bit distressing,” Paul Jacques of Island Conservation noted a couple days before we were to depart for Kamaka Island to try to start a new colony of endangered Polynesian Storm-petrels. He was describing his past experience sleeping on the island. “You might want to sleep in a tent if you don’t like that sort of thing.”

I live in Alaska. I had never heard of Kamaka Island or Polynesian Storm-petrels. Because I know our climate is changing, however, I volunteered to go to Kamaka to help try to save the Polynesian Storm-petrel (or Kotai, as it’s known to the local people) from extinction and restore an important island habitat.

The accelerating rate of climate change can invite despair, but I look for ways to respond. One of the most effective responses is to mend frayed ecosystems. My belief that stronger, healthier creatures are better equipped to survive climate change is supported by decades of science—and well-populated ecosystems are more resilient in turn. I wanted to help endangered Polynesian Storm-petrels survive and also help mend their part of the world.

So, I packed a tent.

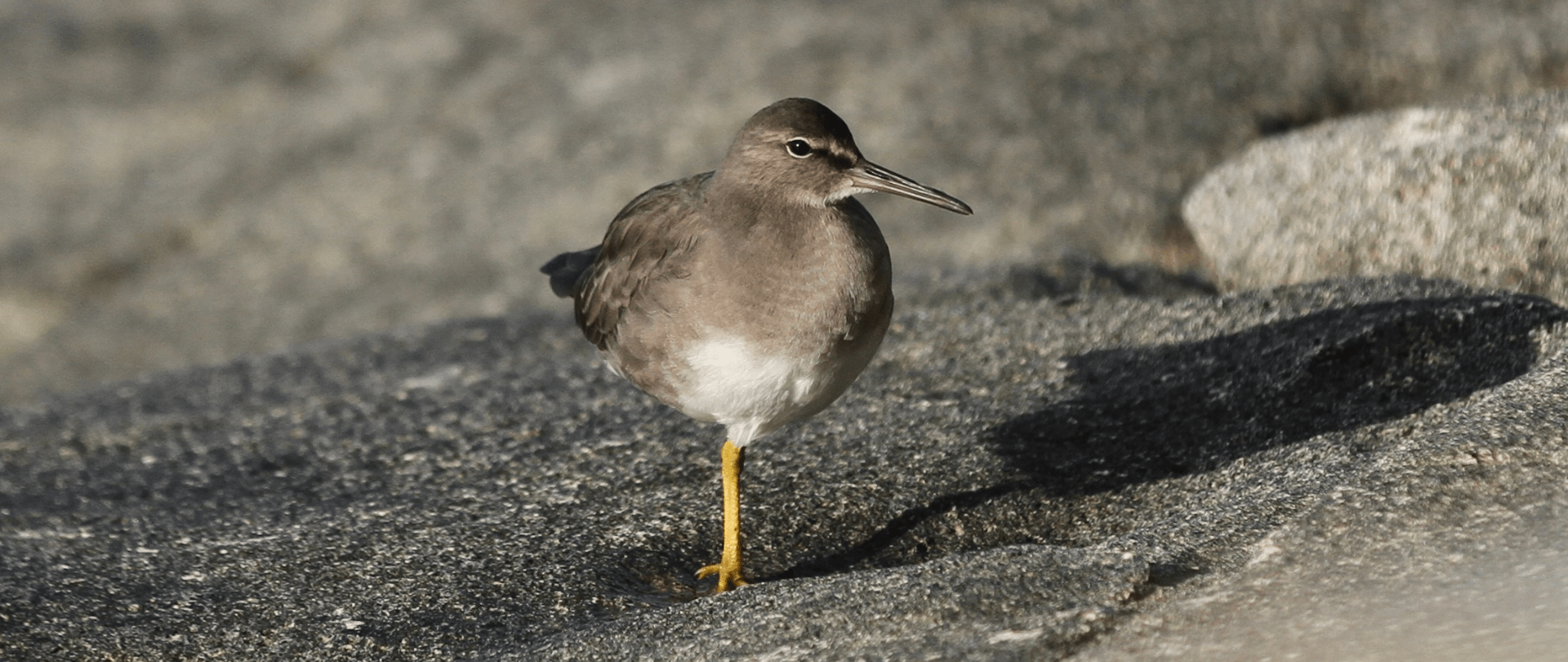

Kamaka is a small island in the Gambier Archipelago about 1000 miles southeast of Tahiti. The southernmost island in the archipelago, it’s a beautiful place. Granted, Kamaka is far from Alaska. But as I expected I would, I easily found connections across even that distance. Birds, for one. I was delighted to see Wandering Tattlers dodging the surf on Kamaka’s shore. They summer in Alaska. The same is true of the Bristle-Thighed Curlew and Ruddy Turnstone. They poignantly reminded me: we all share the same home.

I have not yet seen a Polynesian Storm-petrel, but I’ve learned about them. Because storm-petrels live far out at sea—beyond the continental shelf—and feed at night, they are not well understood. They are rarely seen except before and during storms, when they shelter close to shore—hence their names. When feeding, storm-petrels patter across the waves “grazing” on small creatures such as plankton and crustaceans, which they find using their extraordinary sense of smell. Only nesting brings them to land. The world’s few surviving Polynesian Storm-petrels, estimated to number between 250 to 1,000, build their burrows mostly on a handful of islands in French Polynesia. Because they have no defenses against predators, and they nest on the ground, their home islands must be predator-free.

Until two years ago, Kamaka was not safe for ground-nesting birds. Introduced, invasive rats preyed on the birds’ eggs and young. In 2022, Island Conservation worked with the owners of Kamaka (Tehotu and Raruna Reasin), SOP Manu, Envico, and the town hall of the Gambier to eradicate the rats.

With the rats gone, Kamaka now could be a prime Polynesian Storm-petrel nesting site. Attracting Polynesian Storm-petrels to Kamaka is the first opportunity to try to increase their population by expanding their nesting habitat.

But Polynesian Storm-petrels typically return to the same nesting site every year. Their young likewise typically return to their birth islands. Making Kamaka safe is not enough to help save the birds—we also need to attract them to use it as a nesting site. Because Polynesian Storm-petrels are social birds that nest in colonies, Island Conservation is deploying a “social attraction” strategy using recordings of their calls. The hope is that the recordings will prompt those birds returning to French Polynesia, and specifically those returning to nearby Manui Island, to nest on Kamaka.

Implementing a social attraction strategy on Kamaka was not an easy task. Led by our excellent project manager, Coral Wolf, of Island Conservation’s Impact Team, we first reconnoitered the existing nesting sites on nearby Manui Island and then tramped around Kamaka looking for the best potential nest sites.

Next, frequently working in the rain, we installed solar panels, speakers, cameras, and nest boxes at those sites. Then we checked the sites later in the week at sundown and before sunrise to ensure the petrel calls started broadcasting at dusk and stopped at dawn. Finally, we reviewed the entire setup with Tehotu Reasin, the very supportive owner of Kamaka, so he could monitor and maintain it.

Attracting Polynesian Storm-petrels to Kamaka was not all our five-person team did, however. With work days starting as early as 5:10 am and ending as late as 9:30 pm, we made many trips up and down the steep island every day. We confirmed that there were no more rats. We did daybreak and nightfall bird counts of current bird populations, including the Brown and Red-Footed Booby; Long-tailed Cuckoo; Pacific Reef Egret; Great Frigatebird; Black, Blue-gray, and Brown Noddy; Wandering Tattler; Great-crested and White Tern, White-tailed and Red-tailed Tropicbird; and Christmas Island and Tropical Shearwater (which has perhaps the most maniacal call of any bird I’ve heard. We also did seed counts to assess the effect of removing rats from Kamaka, and collected native grass seeds from near the Polynesian Storm-petrel’s current nesting sites on Manui Island and planted them close to the potential nesting sites on Kamaka.

On our last full day on Kamaka, local team member Barry Mamatui, Paul, and I hiked to the most distant nesting site to retrieve the line we had used to climb the cliff above the nesting burrows there. Task done, we paused atop the ridge—with its view of the archipelago spread below and a soft breeze in our faces. Barry said in this understated way: “Nice place.” Paul and I agreed.

As I turned to hike the ridge trail back to the main track, I was filled with gratitude for the opportunity to work at that “nice place” with people I enjoyed and respected. I left with hope that soon one or two, and someday many, Polynesian Storm-petrels would also find it to be a nice place to nest and safely raise their young.

But establishing Polynesian Storm-petrel colonies on Kamaka will take time. I thought of the words of the Dalai Lama: “Remember you are not alone,” he said in The Book of Joy, “and you do not need to finish the work.” I certainly was not alone during my time on Kamaka. I’m grateful to each person with whom I worked there: Island Conservation’s Paul Jacques and Coral Wolf, and French Polynesian team members Barry Mamatui, Benjamin Paturet, Tehotu Reasin, and Tehani Withers of SOP Manu. And while I had not finished the work of bringing Polynesian Storm-petrels to Kamaka, I left the island confident that others—both conservation professionals and people like me who are just now learning of Polynesian Storm-petrels—one day will do so.

Pictured from left to right: Coral Wolf, Paul Jacques, Jim Torgerson, and Tehani Withers; Coral Wolf, Tehani Withers, Paul Jacques, and Barry Mamatui

Support Island Conservation’s work on Kamaka and other islands around the world today!

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications