The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

November 21, 2017

Written by

Andre

Photo credit

Andre

By: André Raine

I clearly remember my first trip to Lehua. Back in 2011 I went to the islet for a four-day seabird monitoring trip, and it instantaneously became one of my favourite places in the main Hawaiian islands. From the boat Lehua was at first a mere blip on the horizon, but as time progressed it got bigger and bigger until its steep and barren slopes reared up above us. Seabirds swirled everywhere – the albatross were gone for the season (it was September), but Red-footed Boobies dotted the island in their multitudes, Brown Boobies plunged into the water around us, and Wedge-tailed Shearwaters cruised by with a determined expression as they sought their next fishy meal.

Once on the islet, the task of reaching the summit seemed somewhat daunting. It’s hot out there, with little vegetation and no shade – just a long, long trek up a very steep incline, rocks shifting beneath our feet, occasionally dislodging and bouncing down to the azure seas below. Sweating and short of breath we reached the top and there the view took our (remaining) breath away. Lehua is a tuff cone (part of the extinct Niʻihau volcano), and at the top you get a stunning view of the crater. A pod of 150 Hawaiian Spinner Dolphins patrolled the waters below, occasionally breaching the surface with their pirouettes. Above, Great Frigatebirds circled ominously, peering out to sea and waiting for the next hapless booby or tropicbird to arrive.

An amazing place. But while that first trip was enchanting for all of its wildlife, it was also an eye-opener to the grim reality of the peril that faced the seabird colonies there: a shadowy, skittering population of Polynesian Rats that were gleefully consuming seabird eggs and chicks alike.

During the day, we would catch glimpses of them – a rat would burst out from a dry clump of grass, scamper over one of our boots and disappear under the rocks. As our monitoring work progressed, we found Wedge-tailed Shearwater and Red-tailed Tropicbird eggs broken open, the edges gnawed, the insides consumed. Tiny seabird chick bodies were commonplace – pulled out of burrows and half eaten. This was particularly true for the diminutive Bulwer’s Petrel – the vast majority of Bulwer’s Petrel burrows we found had bits and pieces of chick inside. At night, our nocturnal slumbers were regularly interrupted by rats trying to get into food bins, or indeed trotting over us on their nocturnal ramblings.

Six years and many trips to Lehua later, I can personally attest that the threat of rats never abated–most trips were the same—a mixture of wonder at the Lehua seabird spectacle and sadness at the rat predated seabird remains we would find. So, needless to say, I was extremely pleased to hear that a rat eradication project was going to finally go ahead on Lehua in 2017, spear-headed by Island Conservation and the State of Hawaii (for the full list of partners, check out the downloadable “Fact Sheet” and the video.

From start to finish the project was extremely well organised, in terms of the diligence in permitting, the Environmental Impact Assessment, and pre-eradication studies (including rat home range studies, triggerfish studies, and an initial trial drop of poison-less bait to examine if other species might be impacted). A highly trained and dedicated team that included island restoration specialists and the people of Niʻihau was established and the three rat bait drops were a master class in co-ordination and precision. And now, we all wait to see if it has been successful.

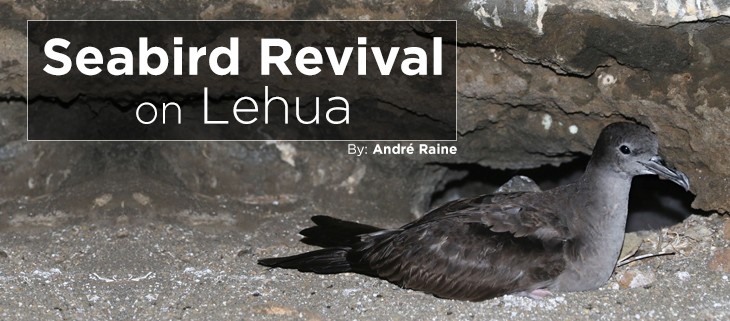

A few weeks ago, I went out to Lehua again for one of our annual monitoring trips – the first time on the islet since the bait drop. I was very keen to see how the islet looked now that the operation was over. We worked our way over the islet for four days, scouring the slopes and ridges, collecting data from our usual 75 permanent seabird plots for ground nesting seabirds. The birds were there when we got there, boobies watching us pass by with open curiosity, tropicbirds giving us hell when we walked near a nest, frigatebirds prowling the skies. Fat, healthy Wedge-tailed Shearwater chicks shuffled about in their burrows looking like animated fuzzballs. One of our burrow cameras showed a Bulwer’s Petrel chick exercising outside its burrow and actually fledging – a great omen, as this is something we have never recorded on our cameras in previous years!

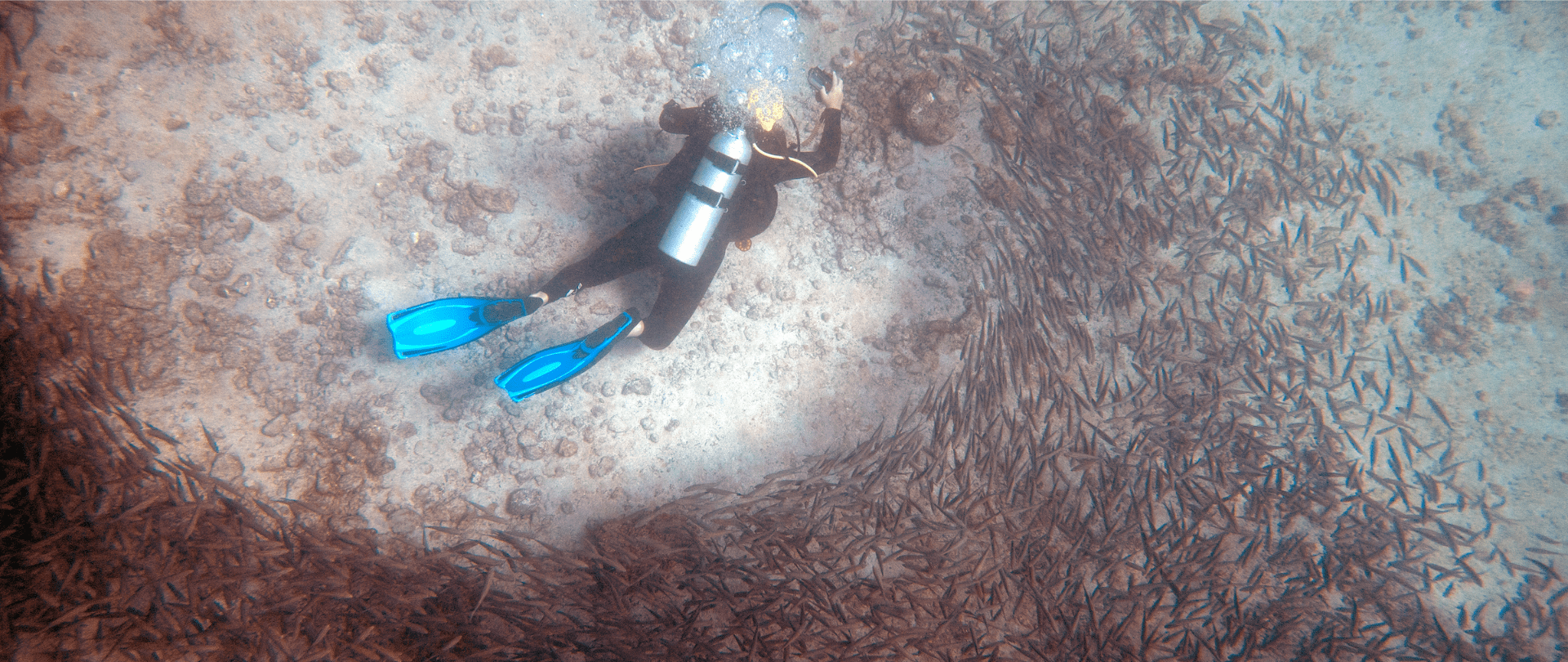

The seas around Lehua were also thriving with life as usual – White-tipped Reef Sharks cruising by, Hawaiian Monk Seals lounging about on the shores or slipping into the water for a quick swim, schools of reef fish giving the waters a riotous dash of colour. The islet was beautiful as ever. But one thing was missing – rats. Not a rat to be seen across the length and breadth of the islet. Occasionally we would find the body of one, long dead. But no shadowy rodents anywhere. They were remarkable in their absence.

This doesn’t of course mean they are definitively gone – rats are notoriously cunning after all. It’s too soon to tell and Island Conservation will be undertaking intensive monitoring studies on the islet in the future to assess whether or not the eradication has been a success. We will also be in a position to see how the eradication project went with our own annual monitoring plots next year. If rats are truly gone, we should see more eggs hatching and more chicks fledging. The breeding colonies of Bulwer’s Petrel and the endangered Band-rumped Storm-petrel (two species particularly vulnerable to rat predation) should increase dramatically in numbers, and there is even the possibility of Lehua being colonised by seabirds that should be there but have been kept at bay by ratty hordes, perhaps Blue-gray Noddies or Sooty Terns. And with no rats to nibble on seedlings and seeds, native plants should start to thrive again.

So, fingers crossed for the future of Lehua – it’s been a long, well-planned, and much needed project to eradicate rats on the islet. Let’s hope next year sees confirmation of success, and a new dawn for the seabirds out there.

Featured photo: A Wedge-tailed Shearwater adult waits outside its burrow on Lehua Islet. Credit: André Raine

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!