December 4, 2024

The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Our new online shop is live!

This was something we had never expected to occur. Mice preying on adult albatrosses simply hasn’t been recorded here.”

– US Fish and Wildlife Service

From the surface, Midway seems like a pristine place; but a closer examination reveals a colorful past and layered landscape. Restoration of this island system has been an ongoing (and challenging) activity since Midway’s transfer to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1996. Islands are dynamic places, quick to change and quick to respond. But, in the winter of 2015, something unexpected happened on Midway.

Volunteers were counting all of Midway’s albatrosses as part of the Annual Albatross Census. As they traversed the islands, they began to notice bloody wounds on the backs and necks of albatrosses. Fearing the worst, USFWS biologists assumed a rat had somehow made its way onto remote Midway (perhaps by plane or boat) and deployed rat traps and cameras to capture the culprit. The cameras revealed something unexpected, a nasty night-time surprise of house mice (Mus musculus) swarming over Midway’s most iconic and beloved wildlife species—Laysan Albatross. Not having evolved with aggressive mammalian predators, albatrosses lack a defense mechanism to this type of attack. Albatrosses tried to shake off the predatory mice, but most would remain steadfast on their nest while others abandoned their egg after repeat attacks, and some albatrosses even died on their nest. Coupled with their unyielding devotion to their egg and a slow cycle of reproduction, any losses could have cascading effects on the population for years to come.

Mice have been on Midway for several decades—what prompted these sudden attacks?

Invasive house mice and black rats (Rattus rattus) were inadvertently introduced on Midway around 1943 during the peak of U.S. armed forces operations and Midway’s use as a key naval base during WWII. The introduction of black rats led to rapid (and unfortunate) extinction of several species, including the endemic Laysan Rail (Porzana palmeri) and Laysan Finch (Telespiza cantans—which still survives on Laysan Island and Pearl and Hermes Reef). Additionally, Midway’s Bonin Petrel (Pterodroma hypoleuca) population plummeted following the introduction of rats, largely due to their vulnerable burrow-nesting habit. Black rats were successfully eradicated from Midway in 1996, leaving house mice as the only invasive mammalian rodent in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

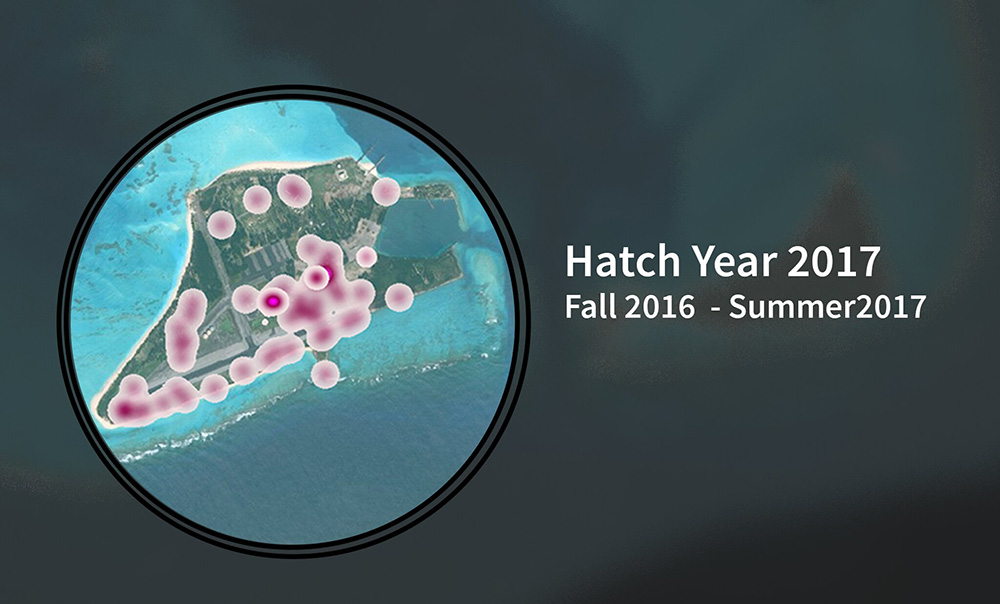

The mouse attacks in 2015 were bizarre and completely unexpected—but what was even more alarming was that in the following winter, the extent and severity of mouse attacks increased dramatically. Originally isolated to the central area of Sand Island, predatory mice were now found biting birds all around Sand Island. During the especially severe mouse attacks in the winter of 2016, USFWS decided to implement control methods in high impact (attack) areas, which resulted in a swift decrease in mouse attacks. Although control has minimized such attacks, but is far from a permanent conservation solution. The final solution—remove invasive mice from Midway.

A mouse, though, is rather small, especially in comparison to an albatross. Mouse attacks on such a large seabird seem surprising and unlikely; however, the evolution of albatross (and other seabirds) in remote locations without predators has resulted in the lack of anti-predator response. In other words, albatross simply do not have an evolutionarily strong fear of predators and therefore have a diminished reaction to swarming mice.

But, it still doesn’t answer why these mouse attacks happened now, and not decades in the past. There are lots of different ideas behind this Midway mouse mystery, most of which revolve around landscape-level changes in habitat, food availability, and weather anomalies. Golden crownbeard (Verbesina encelioides)—an invasive species from the sunflower (Asteraceae) family—once covered upwards of 70% of Midway’s islands but now is virtually absent since control efforts started in 2011. Some think that golden crownbeard might be an important food resource for mice; others think that when golden crownbeard was abundant and formed dense stands, the plants might have supported a thriving population of insects—tasty morsels for hungry mice. So, as field technicians and volunteers sprayed and pulled golden crownbeard, the weed became scarcer and scarcer—and perhaps, too, food resources for mice. And when food became especially uncommon during the winter months, mice may have switched to a new and widely available food source: albatross. It’s certainly not unheard of, similar and shocking phenomena have been observed on Gough and Marion Islands in the Southern Indian Ocean, with predatory mice targeting seabirds when food plummets during the winter.

To ensure a robust albatross breeding colony into the future, we need a permanent fix. Action is needed now. Island Conservation and our partners are going to remove predatory mice in July 2020 and restore the balance on the Atoll, but we need your help. Learn more at http://www.noextinctions.org/.

Featured photo: Laysan Albatross adult and check. Credit: Tom Green

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications