New Tech for Island Restoration: Sentinel Camera Traps

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

March 7, 2017

Written by

Sara

Photo credit

Sara

Tucked away among the shelves of a museum in Paris for 140 years was a new discovery waiting to happen. To the untrained eye, it would appear to be just another beetle in a diverse collection. But in fact, there was something more to this particular specimen.

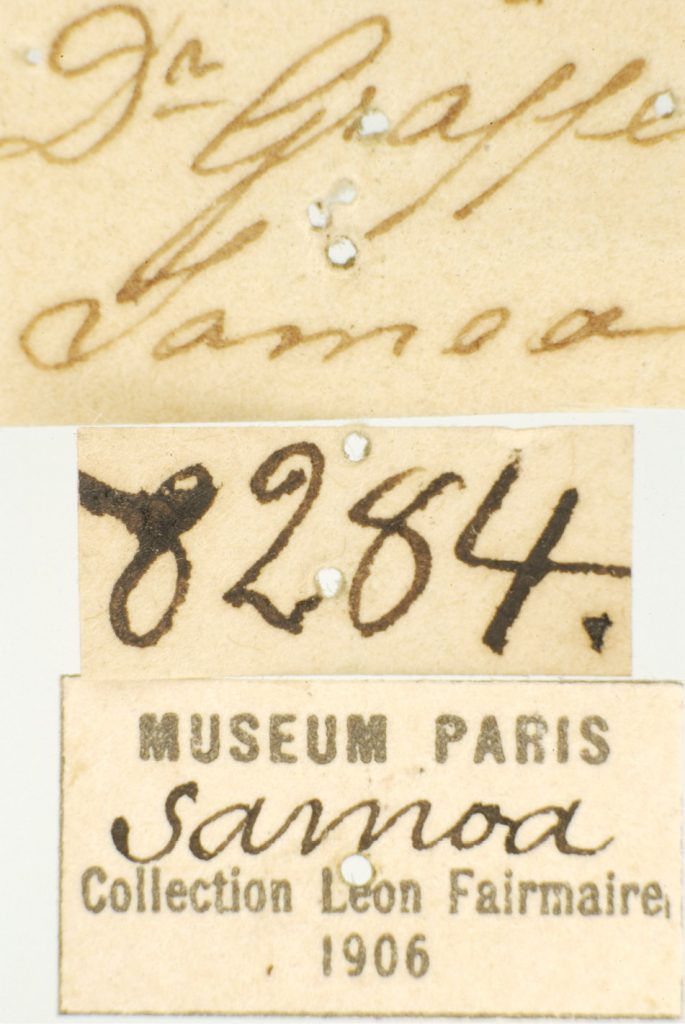

The story begins sometime between 1862 and 1870 when Dr. Eduard Graeffe, a Swiss zoologist and naturalist, was working in the field in Samoa. He came across a large beetle, and added it to his collection, which included specimens from Australia, Fiji, Tonga, and Samoa.

His collection ended up in his employer’s museum–Museum Godeffroy. Johann Godeffroy is believed to have subsequently loaned or sold Graeffe’s collection of beetles to French entomologist Leon Fairmaire. Fairmaire, if you’re not familiar, wrote 450 papers on beetles in his lifetime. Upon Fairmaire’s death, the so-named “Fairmaire Collection” of beetle specimens collected by Graeffi was transferred to the National d’Historie Naturelle (French National Museum of Natural History) in Paris.

Decades later, in 1971, entomologist Terry Erwin and his wife visited the museum and assessed the condition of the Fairmaire Collection. Their review was not exactly glowing. They described the shelves and boxes as being in poor condition with missing or low-quality labels. “A mess!” they wrote. The large tropical beetle originally collected by Graeffe carried on in its anonymity. Its identity remained a mystery until decades later, another scientist entered the scene.

Entomologist James K. Liebherr of Cornell University is an expert in carabid beetles of the Society and Hawaiian Islands, and curator of the Cornell University Collection. Liebherr has regularly visited the French National Museum of Natural History to borrow specimens for research. During one visit, he came across a large beetle he didn’t recognize. He had not seen it mentioned once in any literature he had read.

To find out more about the mysterious member of the collection, Liebherr performed a phylogenetic analysis. He collected data from 49 different beetle species to input into a computer algorithm that would link up all the species into a network. The network, called a phylogenetic tree, represents a scientific hypothesis of the evolutionary history of the various species. The placement of a species in relationship to other species is the key to meaning in the biological world. In the research paper, “Bryanites graeffi sp. n. (Coleoptera, Carabidae): museum rediscovery of a relict species from Samoa,” published in the scientific journal Zoosystematics and Evolution, Liebherr notes:

It is not the simple naming of organisms that occupies systematists, but more importantly, the organized naming and placing in context of all organisms.

Based on his analysis of 127 morphological characters from 49 specimens of the carabid beetle tribe Platynini in the Austral-Pacific region, Liebherr concluded that the one mysterious individual belonged to a Samoan lineage of the genus Bryanites. Only two specimens in existence were previously known to belong to the Bryanites genus. They were collected in 1924 by entomologist E.H. Bryan Jr. in Samoa. The specimen in question, however, was not exactly like the other Bryanites. It was unique–a new species. Its name? Bryanites graeffi–in honor of Eduard Graeffi, the original collector.

A new species discovery is always thrilling. However, the excitement of a new discovery does not much soften the disappointment in learning that the species is long gone. Based on fieldnotes and fossil record analysis, Bryanites graeffi is believed to have already gone extinct.

To understand why Bryanites graeffi went extinct, we can trace its story back to Samoa in 1924. Field notes from entomologist E.H. Bryan Jr., who discovered the two specimens belonging to the genus Bryanites, offer a major clue as to what could led to the disappearance of the large tropical beetle. His notes read:

Dug several things from partly rotten bark of large tree; two large landshells [snails] on orange tree in banana patch at about 2200’. [Met] Mr. Beck and returned to hut. Moquitoes not bad, but rats after our provisions.

According to Liebherr, presence of rats, which feed on carabid beetles, shrinks native carabid beetles’ chances of survival. Liebherr points out in his paper that a known fossil record on Kauai indicates disappearance of carabid beetles following the arrival of humans and the rats that traveled with them. He added:

Similar extinctions have been recorded for Hawaii; all occurring during the time of human colonization and attendant introduction of the Pacific rat.

Liebherr notes that another type species went extinct in Apia, the capital of Samoa and the same place Bryanites graeffi was collected: the Flying Fox Pteropus allenorum. Considering the popularity of the spot with westerners, it’s not all that surprising that extinctions have taken place there. Invasive species, such as rats, can span the globe by stowing away in ships or other craft. These particular invaders are well known for their damaging effects on island ecosystems. Liebherr noted:

The presence of predatory, climbing, night active rats is uniformly deleterious to native communities on tropical islands.

The extent of ecological damage that can be done quickly by invasive rats is illuminated in this story particularly because extinction of beetles is unusual. They are extremely adaptable and have persisted through significant environmental changes throughout Earth’s history. But, like many native animals threatened by invasive species, they simply cannot adapt quickly enough to unprecedented predators like invasive rats. It is unknown whether all Bryanites species are extinct of if some still persist today.

Though Bryanites Graeffi is believed extinct, there is still a chance to learn more about it if fossil remains are discovered. Liebherr notes that Samoan subfossil deposits may contain further evidence of the beetle, and could reveal more about its mysterious past.

Although Bryanites graeffi is believed to be extinct, the process of identifying this unique species has yielded valuable insight. The research reveals that Samoa supported a unique radiation of beetles. It also supports the notion that biodiversity in Samoa and nearby areas began to decline following human colonization.

Biodiversity enriches our world and enables ecosystems to function. Invasive species are the number one driver of island extinctions, and likely the reason for the extinction of Bryanites graeffi. By removing rats and other invasive species from islands, further loss of rare native wildlife—including species that we don’t even yet know exist—can be prevented.

This brings us to the final lesson learned from this new research: Liebherr’s discovery highlights the importance of natural history museums. We know so little of the biodiversity surrounding us—the hope for new species discoveries burns bright. There may be all sorts of surprises lurking in the corners and corridors of our museums. In Liebherr’s words:

Natural history museums represent invaluable and irreplaceable archives of biological diversity on Earth.

There’s no telling what will be discovered next, or where, or by whom. We can look forward to what the next discovery will teach us about the incredible planet we share with a wide variety of creatures, great and small.

Featured photo: Bryanites Graeffi. Image from Bryanites graeffi sp. n. (Coleoptera, Carabidae): museum rediscovery of a relict species from Samoa”

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…