March 11, 2025

Press Release: New eDNA Tool Can Detect Invasive Rodents Within an Hour

New environmental DNA technology can help protect vulnerable island ecosystems from destructive invasive species.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Looking to make an impact this Earth Month? Here’s how.

The Monito Gecko, a small reptile, endemic to Monito Island, Puerto Rico, has officially been delisted under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), joining the ranks of the Bald Eagle and the Brown Pelican.

Since 1982, the Monito Gecko has been protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), threatened with extinction largely due to predation by invasive rats. To protect Monito Island’s unique fauna including the Monito Gecko, the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (PR-DNER) worked to remove invasive rats from the island. In 2014, PR-DNER and the USFWS officially declared Monito Island free of invasive rats—eliminating the geckos’ greatest threat to survival.

In 2016, Island Conservation joined the USFWS and PR-DNER on a monitoring trip to Monito Island to determine the population of the Monito Gecko. Today, there are an estimated 7,600 geckos on the Island—a population stable enough to warrant delisting, making the Monito Gecko the first Caribbean endemic species to be delisted under the Endangered Species Act.

Since the creation of the Endangered Species Act in 1973, it has successfully prevented the extinction of at least 99% of species listed as of 2013, but very few species have been removed from the list because of recovery. The Monito Gecko is now one of these few species along with Bald Eagles and other iconic wildlife that has been protected and ultimately removed from the ESA list due to conservation and habitat protection.

This action is the most recent recovery success of a species thanks to the collaboration of conservation agencies and organizations, and demonstrates how well the ESA works in wildlife protection.”

Bryan Arroyo, Deputy Director of the USFWS

An adult Monito Gecko is only about an inch and a half long and would fit on your index finger and still have spare space. Its name comes from Monito Island which it is endemic to, a karso rock covered in dry, forest, shrub vegetation.

Monito Island as a nature reserve, designed to protect native wildlife and vegetation. In addition, to the Monito Gecko, the Island is home to one of the largest seabird colonies in the Caribbean. Along with this, two other unique, endangered species: the Lady Bird of Puerto Rico and the prickly cactus pear.

The USFWS, DRNA and other groups will continue to monitor the gecko population to ensure long-term viability and maintain biosecurity protocols to prevent the reinvasion of rats.

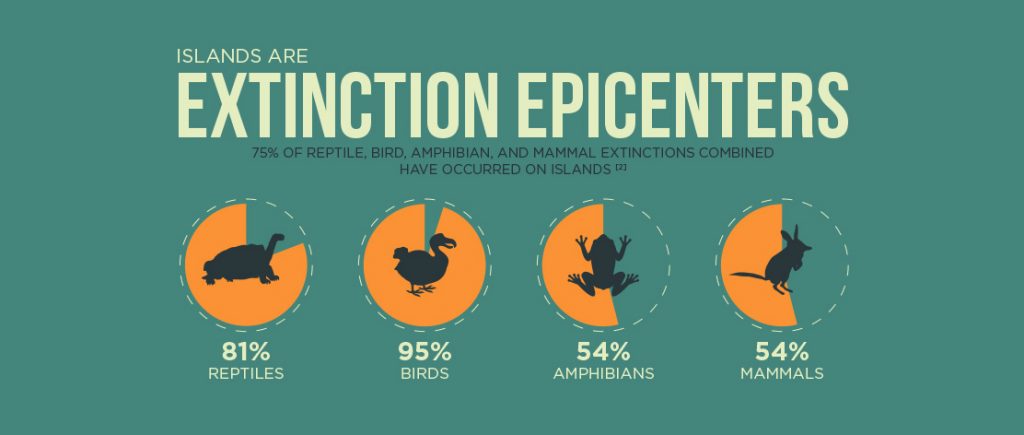

Islands represent both a unique conservation need and opportunity. Islands total only a small fraction of our planet’s land area and host a disproportionately higher rate of extinction and endangerment per unit area than continents. For this reason, investing limited conservation funds on islands provides a high return on investment.

Invasive alien species are a major driver of species extinctions on islands, particularly invasive mammals.

Islands offer hope that we can prevent extinctions and protect biodiversity.

Featured photo: Monito Island. Credit: USFWS

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications