The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

October 3, 2019

Written by

Cielo

Photo credit

Cielo

By: Cielo Figuerola

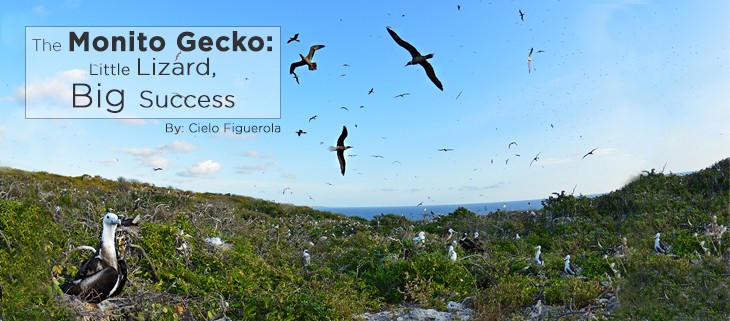

When observed from the air, Monito Island looks like a dot in the Caribbean Sea. You would have to continuously zoom in on any map just to see where it is. Only 5km apart from Mona Island, this 16ha limestone plateau surrounded by vertical cliffs is a haven for seabirds. Monito Island harbors one of the largest seabird nesting colonies in the Caribbean and is designated, along with Mona Island, as an Important Bird Area.

Hundreds of Red-footed, Masked, and Brown Boobies, as well as Frigatebirds can be seen flying over the island, almost forming a black cloud on top of it. On Monito Island you can also find one of three remaining natural populations of the threatened Higo Chumbo cactus, which is endemic to Puerto Rico and needs all the healthy habitat it can get. While these diverse inhabitants make Monito an ecologically significant place, it’s not until you get to know this next native species that you can truly appreciate the island’s importance.

Meet the Monito Gecko, a small, grey lizard with dark spotting. This little lizard is found nowhere on Earth except Monito Island! Due to the rarity of the species and the remote location of the island, not much is known about this gecko. It is believed that, similar to other geckos, it feeds on small insects and invertebrates and that females lay one or two eggs that hatch in two to three months.

Potential natural predators of the Monito Gecko may include other native lizards present on the island: an anole and a skink. Unfortunately, the Monito Gecko has been impacted by an unnatural predator: invasive black rats. Invasive rats were first observed in high densities on Monito in 1969, and by 1974, scientists were already suggesting that a project to remove the invasive rats should be seriously considered due to their impacts on the isolated and fragile island ecosystem. The rare, endemic Monito Gecko was listed as Endangered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1982 with a Recovery Plan finalized in 1986.

Given Monito Island’s unique fauna and the Endangered status of the Monito gecko, the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (PR-DNER) began a series of eradication campaigns for invasive rats on Monito Island from 1992 to 1999.

In May 2014, PR-DNER and USFWS partnered to conduct a systematic rat monitoring survey and could officially confirm and declare the island rat-free! This was a major milestone on the road to recovery for the gecko and other species on the island.

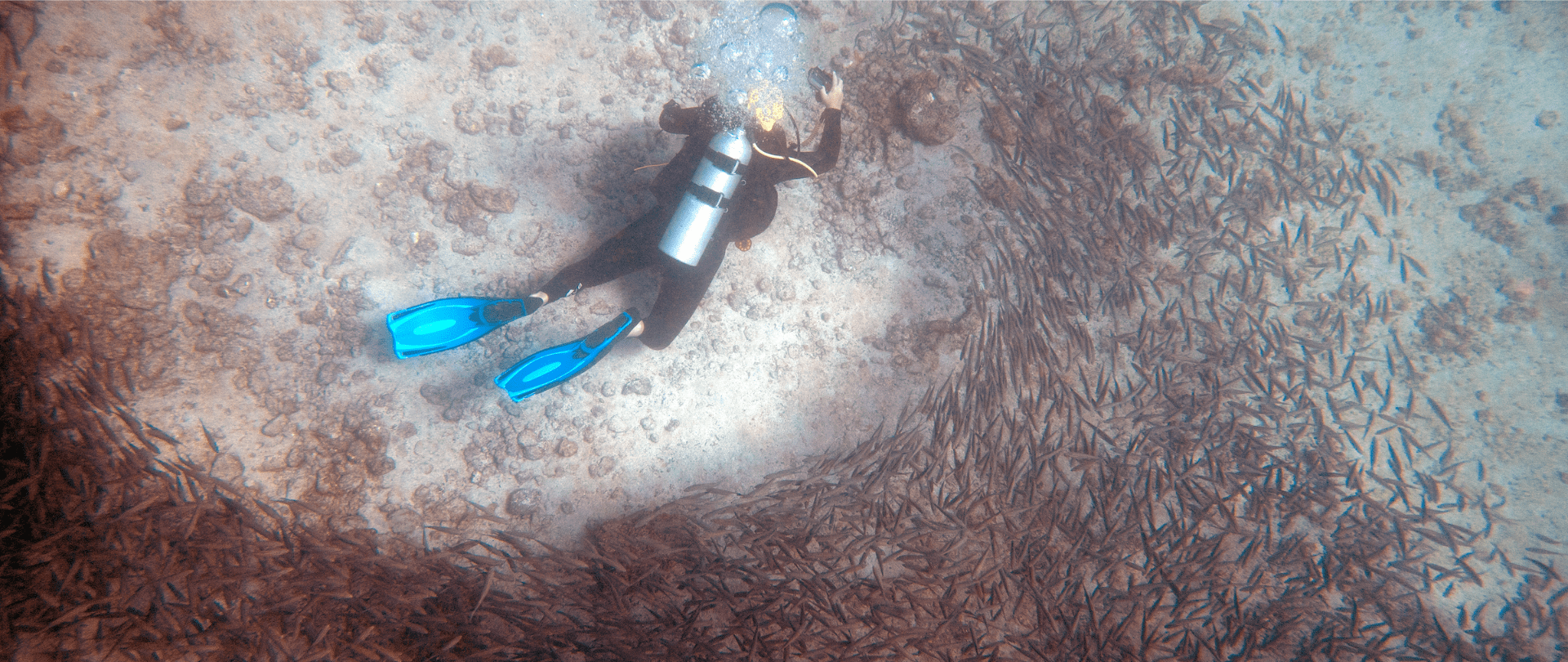

Following this great achievement, a big question arose: how do we know what the status of the gecko is now that rats are gone? To address this, USFWS, PR-DNER, and Island Conservation set out to Monito Island to conduct a systematic survey of the gecko population to determine its status and estimate its population size.

When we set out for Monito, our boat was full to the brim of our camping and field equipment as well as food and water to keep us nourished while we conducted gecko surveys. I was eager to set foot on the island—Monito has been a Natural Reserve administered by the PR-DNER since 1986. There are no facilities or structures on the island—it is truly a wild place.

Our plan was to camp inside the only cave large enough to support our group of eight people. I would say that the most difficult part of the whole trip was probably getting on and off the island; Monito is surrounded by 66m high cliffs. Fortunately, there is one rock that sits close enough to the water that boats can carefully get close to it and you can jump and start climbing the wall carrying all the supplies—this, however, is only possible in calm sea conditions. In 1607, explorers were allegedly already commenting on this challenge, saying “we had a terrible landing, and a troublesome time getting to the top of the mountain; (it) being a high firm rock, steep, with many terrible sharp stones. A diverse and thriving sea bird colony undoubtedly owes its presence in part to these sharp cliffs.” Of course, once you reach the top and see the incredible seabird colony and amazing views, things get better.

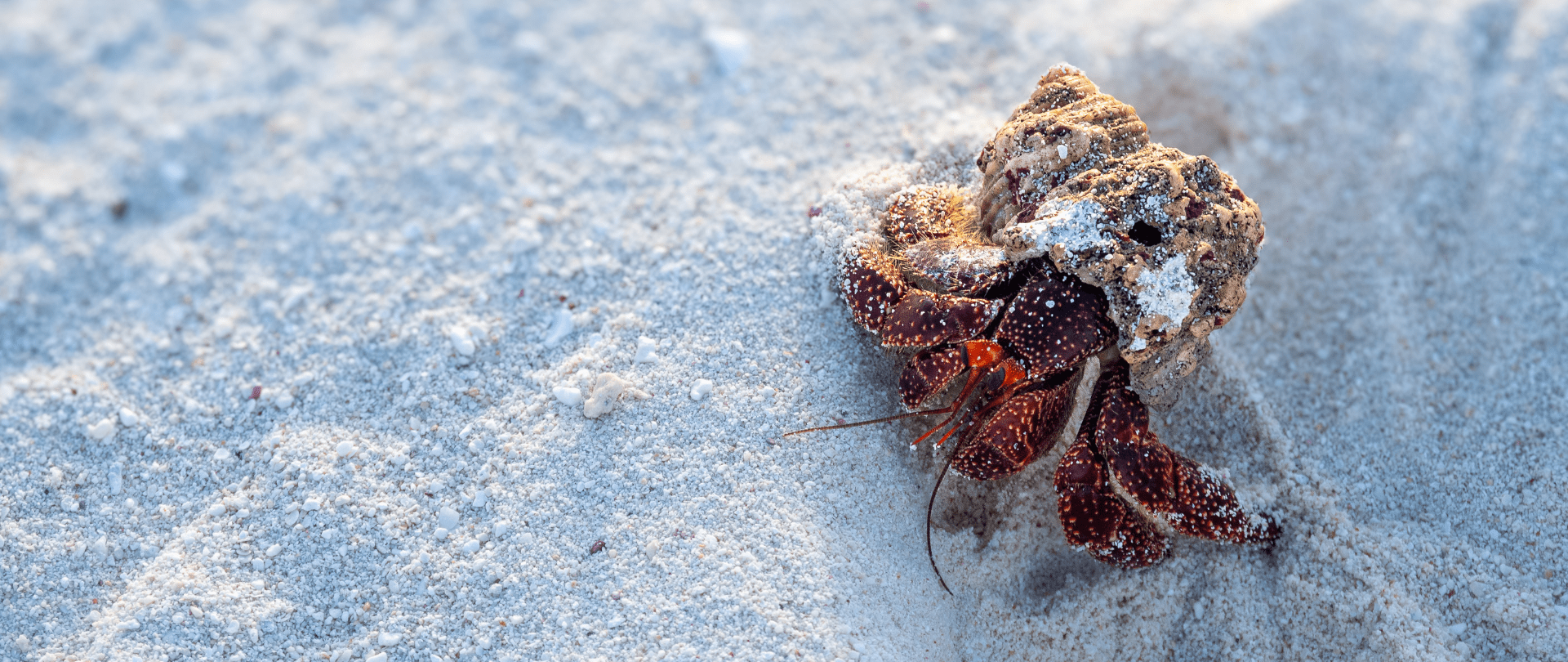

The following days consisted of setting up plots and conducting surveys at night, when the gecko is known to become more active. Conducting fieldwork at night gives you such a different perspective and awakens the senses in a new way—you start hearing and seeing creatures you wouldn’t otherwise notice. We noticed hundreds of land crabs exhibiting an array of colors only the rainbow matches, crickets and other insects foraging, seabirds returning to their colony to sleep, and the sky at night, so bright and yet so dark, making you wish you could just stay there and gaze upward forever.

The survey yielded exactly what we hoped for: the Monito Gecko was found in abundance and was widely distributed on Monito Island. We found that the population was in a good enough shape to be delisted from the Federal List of Endangered and Threatened Wildlife (FLETW) under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). This makes the Monito Gecko the first Caribbean endemic federally listed species to be removed from the ESA. This determination is based on scientific reviews that indicate the species has recovered and the threats to this species have been sufficiently eliminated or reduced. The gecko population will still be monitored for the next five years to ensure its status continues to be adequate.

The series of events that led to the potential delisting of the Monito gecko reminds us of the significant and transcendental results we can achieve through invasive species removal projects on islands. We look forward to applying the lessons learned from this successful journey to other islands where unique species still need our help.

Featured photo: Seabirds fly over Monito Island. Credit: Jan P. Zegarra/USFWS

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!