The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

October 9, 2019

Written by

Wieteke Holthuijzen

Photo credit

Wieteke Holthuijzen

Midway is the world’s largest albatross colony and provides globally significant breeding grounds and migration stopover points for more than 3 million birds from nearly 30 different species. Midway is a “seabird island,” because seabirds function as keystone species—many other species depend on albatross and other seabirds that bring marine-derived nutrients via guano (bird poop) as well as fish scraps. Seabirds largely drive these island systems where ecosystem function, structure, and processes are largely nutrient-dependent. In, the nutrients brought in by seabirds support extraordinarily abundant populations of insects, amphibians, plants, and a host of other species on seabird islands.

Midway’s unique assemblage of flora and fauna make it an important laboratory for restoration ecology and conservation science. Insects, often overlooked, are especially unique in island ecosystems.”

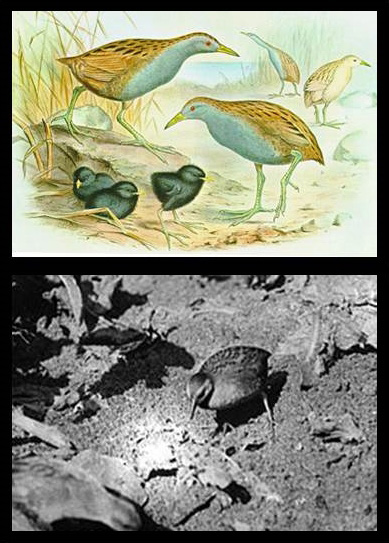

Now, seabirds are specifically adapted to a life at sea and typically breed on remote, isolated islands. However, seabirds are also particularly vulnerable to introduced mammals because they lack appropriate anti-predator behavior and response. Because seabirds evolved in remote island systems, they typically didn’t come into contact with mammalian predators, like rats and cats; therefore, they did not evolve a sense of fear for these kinds of animals. Consequently, when mammalian predators were introduced on islands, seabirds and island birds were the first to go. It only took about 18 months for the rats accidentally introduced to Midway Atoll NWR in the 1940s to completely wipe out healthy populations of both the Laysan Rail (Porzana palmeri) and the Laysan Finch (Telespiza cantans).

In fact, invasive rodents are likely responsible for the greatest number of island bird extinctions as well as disrupted ecosystem functions. Out on Midway, invasive house mice have started to attack and kill adult seabirds—consequently, plans are underway to remove invasive mice in 2020. Since mice are relatively small and cryptic, and because we wouldn’t expect such a small mammal to attack such enormous prey—they are a very understudied rodent.

Now, you’re probably thinking how do bugs play into this? And why do we care?

Seabird islands depend heavily on marine nutrient inputs, but bug communities are key to island ecosystems by processing these nutrient inputs and making them biologically accessible. As insects break down these nutrients, nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus can enter the soil and be absorbed by plants. In turn, plants support bugs of all types, which are often consumed by local fauna (or, in the case of Midway, local Laysan Ducks or migratory species, such as Bristle-thighed Curlews and Pacific Golden Plovers). Plants also serve as important nesting habitat by providing soft grasses to line the nest cups of albatross or sturdy root structures to create a strong burrow for ground-dwelling Bonin Petrels.

Bugs also occupy key roles in ecosystems such as detritivores (feeding on dead organic matter, especially plants), herbivores, predators, prey, pollinators and more. Since bugs have so many functions in a given ecosystem, any effects at these functional levels may have implications for other parts of the ecosystem. After all, as John Muir wrote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.”

If we only focus on the physical, visceral impacts of mice such as the visible attacks on albatross, we’re missing out on the larger picture and broader implications of invasive mouse impacts on Midway’s ecosystem. As part of this eradication, we (Dr. Holly Jones Evidence-based Restoration Lab) are helping to coordinate ecological monitoring on Midway to understand the hidden impacts of invasive mice on islands by studying the direct and indirect effects of mice on Midway’s ecological components.

Our main objective with this particular project is to monitor Midway’s bug communities before and after the removal of invasive mice to document changes in diversity (Are mice suppressing certain bugs or letting others be released?) and community composition (What bugs are associated with one another and between Midway’s islands—and what bugs might be affected by mice?). A particular pest of interest is the Emerald Beetle (Protaetia pryeri), a major fruit pest that goes after papaya, guava, and a wide range of exotic fruits. This is an especially large and slow-moving beetle—and also a tasty morsel for mice. If mice are consuming this beetle, the mice might be keeping a kind of “control” on the beetle’s population; but, once mice are removed, we might have to prepare for more invasive Emerald Beetles. Conducting these kinds of ecological studies are critical to understanding how islands such as Midway work and how we can fine-tune conservation to achieve the most success.

To study bugs, we have a series of pitfall traps that are maintained throughout Midway. Pitfall traps are a very simple contraption—basically, a cup in the ground. Ground-dwelling bugs walk along the surface, fall into the cup, and then are unable to get out. Pitfall trap samples are then sent to Illinois, where myself and my undergraduate students sort bugs, ID, bugs, and count bugs. Currently, we’ve counted over 140,000 bugs—and we’re just about halfway through the study (thanks to the many NIU undergraduates helping on this project)! As the study continues, we will get a better picture of how Midway’s bug communities look like between islands and what we might expect to happen to bug communities after the eradication.

This kind of conservation science is important in that we can predict what could happen to Midway and other islands following the removal of invasive mice, prepare, and ensure a robust and resilient island ecosystem into the future.

But, we need your help to make Midway’s restoration a reality. Learn more at www.noextinctions.org.

Featured photo: White Tern chick perched on a branch on Midway Atoll. Credit: Dan Clark/USFWS

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…

Island Conservation accepts cryptocurrency donations. Make an impact using your digital wallet today!

For Immediate Release Conservation powerhouse BirdLife South Africa has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC) – a global initiative aiming to restore, rewild and protect islands, oceans and communities – to support its work to save internationally significant albatross populations…