January 15, 2025

We’re Joining the Global Rewilding Alliance!

We're joining the Global Rewilding Alliance, a network of environmental organizations around the world!

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Our new online shop is live!

Nathaniel Hanna Holloway, from the Sandin Lab at the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, was part of marine monitoring that occurred in the Galápagos as part of the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge. Read about Nathaniel’s experience and the essential connection between land and sea that makes Scripps, and the Charles Darwin Foundation‘s Marine Biodiversity Research Team, important partners to Island Conservation!

Flying into the Aeropuerto Ecológico Galápagos Seymour on the island of Baltra, our team was greeted by an unexpected landscape. The landscape was rocky, brown, and barren with little vegetation and contrasted by the familiar turquoise and deep blue colors of the sea. Our lab, the Sandin Lab at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, studies coral reefs and how they grow and change over time under a variety of conditions and locations. Most of our field research sites are your typical lush, green, tropical islands, and this landscape initially appeared quite different.

After months of planning, my colleague Nicole Pedersen and I had finally arrived. We were here as part of the marine monitoring, team conducting pre-restoration surveys for the Floreana Island-Ocean Connection Challenge Project. The Island-Ocean Connection Challenge is a program that partners Scripps Oceanography, and non-profit organizations Re:wild and Island Conservation, to remove invasive species from islands to restore native species to benefit wildlife, coastal ecosystems and communities.

We lugged our multiple bags full of SCUBA and underwater imaging gear from bus, to ferry, and then into a taxi to get from the airport to town. The drive was fascinating! We travelled through several different microclimates that starkly contrasted the landscape we encountered at the airport. We were quickly realizing this field expedition was going to be like none we had been on before.

Thanks to our Island Conservation partners, who introduced us to the Marine Biodiversity Research team at the Charles Darwin Foundation (CDF), we had a great new team of collaborators. After a few days of training and getting acquainted, we were ready to board our research vessel and begin collecting a suite of data for our baseline, pre-restoration monitoring. We spent the next 8 days and nights collecting and processing data to describe the impact of the restoration on the fish and benthic communities and nutrient availability in the nearshore marine environment.

We are using a Before-After Control-Impact, or BACI, experimental design to assess the impact of the island restorations. The BACI approach allows for any natural or pre-existing differences between sites and can give an estimate of the “true” effect of the restoration. To do this we needed to find an island similar to Floreana (the impact or restoration island) where restoration activities were not taking place. Luckily, the island of Española, the control island, is close by and has a similar environmental context – meaning it is safe to assume the meteorological, oceanographic, and geologic conditions are, and will be, essentially the same throughout the monitoring. This is critical to differentiating the impact of the restoration from changes due to natural or pre-existing conditions. This experimental design is especially important given the unusual conditions the islands are currently experiencing due to El Niño. Having a control and impact/restoration island to monitor takes care of the Control-Impact part of BACI. To satisfy the Before-After part, we selected a similar number of monitoring sites around both islands and we will collect data before the restoration and then come back and collect the exact same data after the restoration.

The days were long and grueling. Luckily, the team from CDF operated like a well-oiled machine and knew the marine landscape like the back of their hand. One of the many exciting things about working with CDF is that we were able to use a subset of their annual marine monitoring sites as our impact assessment sites – this means we have a plethora of historical marine data to help establish a good baseline. Another cool thing about the data we are collecting is the complimentary terrestrial monitoring data, collected by Island Conservation and their local partners. These data will describe the impact on the terrestrial landscape. Combining these two unique datasets will help us as scientists and conservationists better understand the island-ocean connection and how the nearshore marine environment can be impacted by island restorations.

The dives we conducted around Floreana, the restoration island, and Española, the control island, were incredible and quite different from the tropical environments our lab is used to monitoring – the most shocking being the water temperature! Colder water can make quite a difference when you are in the water for most of the day. The composition of the seafloor environment was also starkly different – notably the lack of live coral cover (although there were a few sites that had some quite large Pavona coral colonies) and that the reef was composed of volcanic rock and not calcium carbonate.

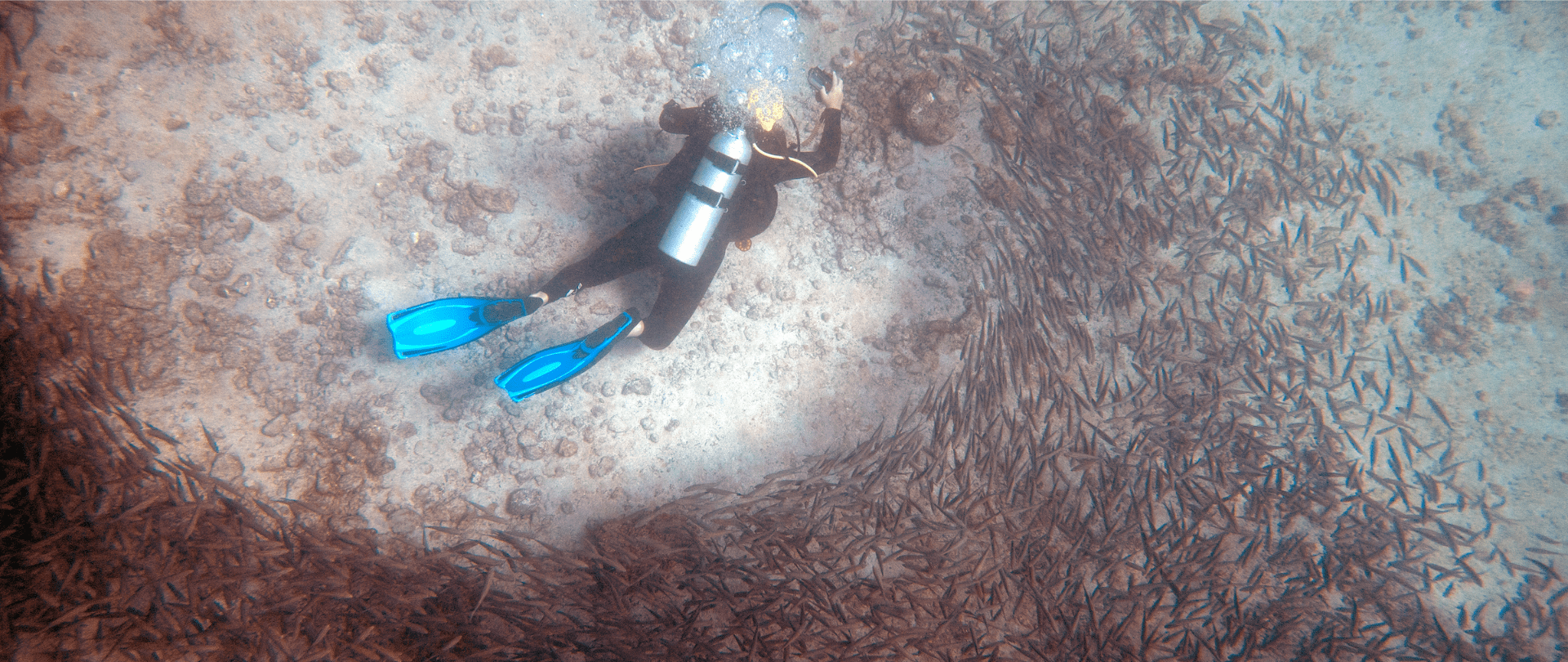

The size and abundance of herbivorous fishes was astounding. On more than one occasion, when we were imaging the seafloor, massive schools of Prionurus laticlavius, or razor surgeonfish, would swim through the plot and completely obscure the seafloor. When this happened, we would have to stop taking pictures and wait for the fish to move on.

As part of our data collection plan, we are collecting samples of macroalgae to process for isotope analysis. Results from the algae isotope analysis will tell us about the source of nutrients and their availability in the nearshore marine environment. Nutrients, and more specifically, the transfer of nutrients from the terrestrial environment to the marine environment, are one of the key connections in the island-ocean connection. Initially, I was surprised with the lack of fleshy macroalgae available to collect, but once I saw the aforementioned schools of herbivorous fishes, I understood why I was having so much difficulty finding sufficient quantities of algae.

One night while anchored off Floreana, the team diligently downloading and entering data and drying and processing algae samples, we were startled when we began hearing loud thumps against the side of the boat. We made our way to the aft deck to see some very interesting shark feeding behavior. What we saw was perhaps 50 or 60 Carcharhinus limbatus, or blacktip sharks, chasing flying fish into the side of the boat. The flying fish would be momentarily stunned and a feeding frenzy would ensue!

The shark feeding behavior was one of the more memorable experiences while we were out of the water. In the water, Nicole and I had a remarkable experience with a curious, playful, and somewhat mischievous sea lion. We were busy collecting images for the large-area imagery models, which are the digital images processed by a computer program that creates a digital twin of the reef and is used for further processing and analysis, when we noticed a few young sea lions zipping around and checking us out. We were both a little startled and nervous as we had been warned that occasionally sea lions can exhibit aggressive behavior and should be avoided. As we continued our dive we noticed that one of our imaging plot corner markers (a float attached to a line to help the image collection diver navigate the plot) was missing. As I was checking the other markers, I saw one of the sea lions swim up to the marker, grab it in its mouth and swim off with it! The mischievous fellow had stolen two of our markers! I followed the sea lion back to where it had nicely placed both markers about 5 meters (16 feet) from the survey site. We got the markers back but that was not the last attempt to steal them! We had to keep an eye out for the playful thieves the entire rest of the dive! It was such a fun and remarkable experience that neither one of us will soon forget.

Having the opportunity to spend time observing and recording data in the Galapagos is especially exciting in light of the IOCC project. The IOCC is a unique combination of good science and good conservation working together to break down the silos between the marine and terrestrial scientific and conservation worlds. Conducting monitoring in a new ecosystem with new partners always leads to new observations and insights. Beyond meeting and working with the team of great scientists and conservationists at CDF, I am especially excited to dig into the data and start quantifying these island-ocean connections and the positive impacts of the island restoration efforts.

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications