Nukufetau Atoll Bolsters Pacific Conservation and Enhances Community Resilience by Removing Invasive Rats

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Our 2024 Impact Report is live!

Published on

August 24, 2023

Written by

Paul Jacques

Photo credit

Paul Jacques

By: Paul Jacques, Island Restoration Specialist

In March this year I first set foot on the coral sand beach of Nadikdik Atoll, the southernmost atoll of the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), a place that was to be home for me for the next five weeks whilst I oversaw of the removal of invasive rats. The Marshalls are a remote collection of low-lying atolls and islets in the central Pacific Ocean, about midway along a line drawn between the top of Australia and Hawaii.

Comprised mostly of ocean, (RMI has the largest portion of its territory composed of water of any sovereign state, at 98%), and with an average land elevation of only 2 metres above sea-level, the nation faces an existential threat from sea-level rise – this is climate change ground zero.

The Nadikdik Restoration Project had been many weeks in the planning, and I had shared numerous zoom calls with my partners from the Secretariat of the Regional Environment Programme (SPREP) and the Marshall Islands Ministry of Natural Resources and Commerce (MNRC) before we finally met in person in the national capital of Majuro. After a week of collecting supplies and finalizing arrangements, our team departed one afternoon on the government boat for an eventful two-day journey south to Nadikdik via the atoll of Mili. As evening approached on the second day, we left the enormous lagoon of Mili to enter the Klee passage and finally come in sight of our destination.

I had studied many images and maps of Nadikdik, but in the late afternoon light, as our boat crept through the shallow pass from the open sea into the azure blue lagoon fringed by thickly forested islands, I was struck by the incredible beauty of this place.

Arriving onshore we immediately doubled the adult population of Nadikdik – a community of just 15 adults and 6 children live permanently here, making their living from harvesting copra, the meat of the coconut, that is dried to be collected and then processed into coconut oil in Majuro.

Copra is the industry of the Marshall Islands – for the outer island communities it is their only source of income, an income that is threatened by non-native, damaging, invasive rats.

Not only do rats consume large amounts of coconut fruit as well as the dried copra product, they also endanger the food security of local communities by ravaging the limited food resources that can be grown in the poor atoll soils, such as breadfruit, pandanus and papaya. For most of us, food security, i.e., the ability to access enough nutritious food to survive, is not an issue – we can pop down to the local store anytime and find the things we need. But imagine if the nearest store were a long boat ride away and only stocked rice, noodles and a few canned items, goods that sometimes don’t even arrive due to the ups and downs of the global markets.

Here self-sufficiency is not a lifestyle choice, it is the only way of life. Homes are built by hand, water is captured from rainfall, electricity is produced from a few solar panels and food is grown from the land and caught in the ocean.

By removing invasive rats from Nadikdik, we would protect the livelihoods of the local community and make conservation gains by safeguarding threatened native biodiversity.

Our first few days were spent setting up camp and training our team. We set up a small village of tents in a clearing next to the homestead of Tana, a local Copra harvester who is expert in the survival skills necessary for atoll living. To cater for the increase in human population, we brought extra hardware from Majuro, and locals and newcomers alike worked side by side to set up expanded solar electricity and rainwater capture systems.

The local community agreed to suspend the copra harvest for the duration of the eradication (to limit the availability of food to rats), and instead they were to become part of the restoration team. We had a big job ahead of us and I was counting on the local knowledge and skills of these hard-working people.

Broadly, there are two ways to remove rats – conservation bait is either spread from the air (by helicopter or drone) or by hand. In both cases it is necessary to get enough bait everywhere – leave a gap in bait coverage and we are certain to fail, as rats can occupy very small territories. For a ground operation like Nadikdik, this means that the treatment area first has to be “gridded” using machetes and surveying equipment, with points flagged every 20 metres, before conservation bait can be spread. I had calculated that across the 100-hectare atoll we would need to mark about 2500 points, which would take the team of 30 about 3 weeks. I had expected a few slow days at the start whilst the team got up to speed, but islanders are quick learners, and the team soon became proficient in using GPS and compass to precisely mark the lines.

Most of the team spoke no English – and I spoke no Marshallese – but by learning a few key words we got along pretty well, although my pronunciation of the Marshallese language caused some confusion.

And so we settled into a pattern, steadily toiling our way along the atoll one islet at a time. We lost a lot of sweat and some blood – I don’t remember any tears, but I’m sure a few of us were crying on the inside at times. The heat was terrific and staying hydrated was a daily challenge; a fresh coconut to drink at lunchtime brought relief beyond words. Coconuts were a hazard too though, and we had to be constantly aware to avoid catching one on the head! The worst hardships were experienced in the labyrinth-like mangroves at the top of the islet, where the sheer number of interwoven stems meant that cutting lines was nightmarish.

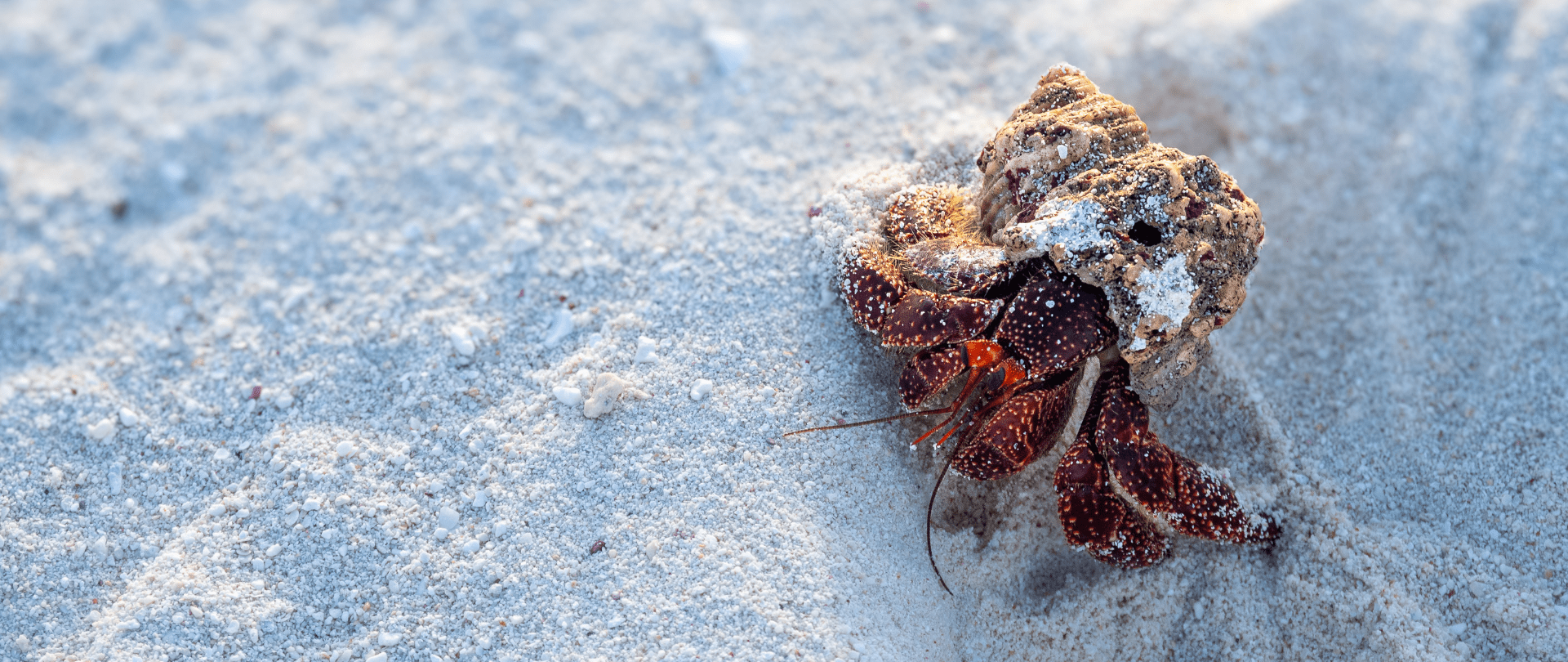

By the end of each day, we would wearily wade back to the boat, (taking care not to step on a venomous stonefish) and chug our way back to camp as the Noddies and White Terns streamed overhead, heading home too to their treetop nests to feed their chicks after a day at sea. I was pleased to find that Noddies, both Black and Brown, remained in reasonable numbers on Nadikdik, though their population must be much lower than historically due to continuous depredation by invasive rats and feral cats. By contrast, ground-nesting seabirds were all but absent, with only a few pairs of Black-naped Terns seen on remote sandbars that were inaccessible to feral pigs, feral cats and rats.

There were no petrels, shearwaters, boobies, sooty terns – the list goes on. Whole groups of species are missing from this atoll, and it is by these absences that we see the effect of introduced mammals and understand the damage that has been done to this ecosystem.

I am lucky to have visited some invasive species-free islands and experienced firsthand the almost unbelievable abundance of lifeforms that make up an intact island ecosystem.

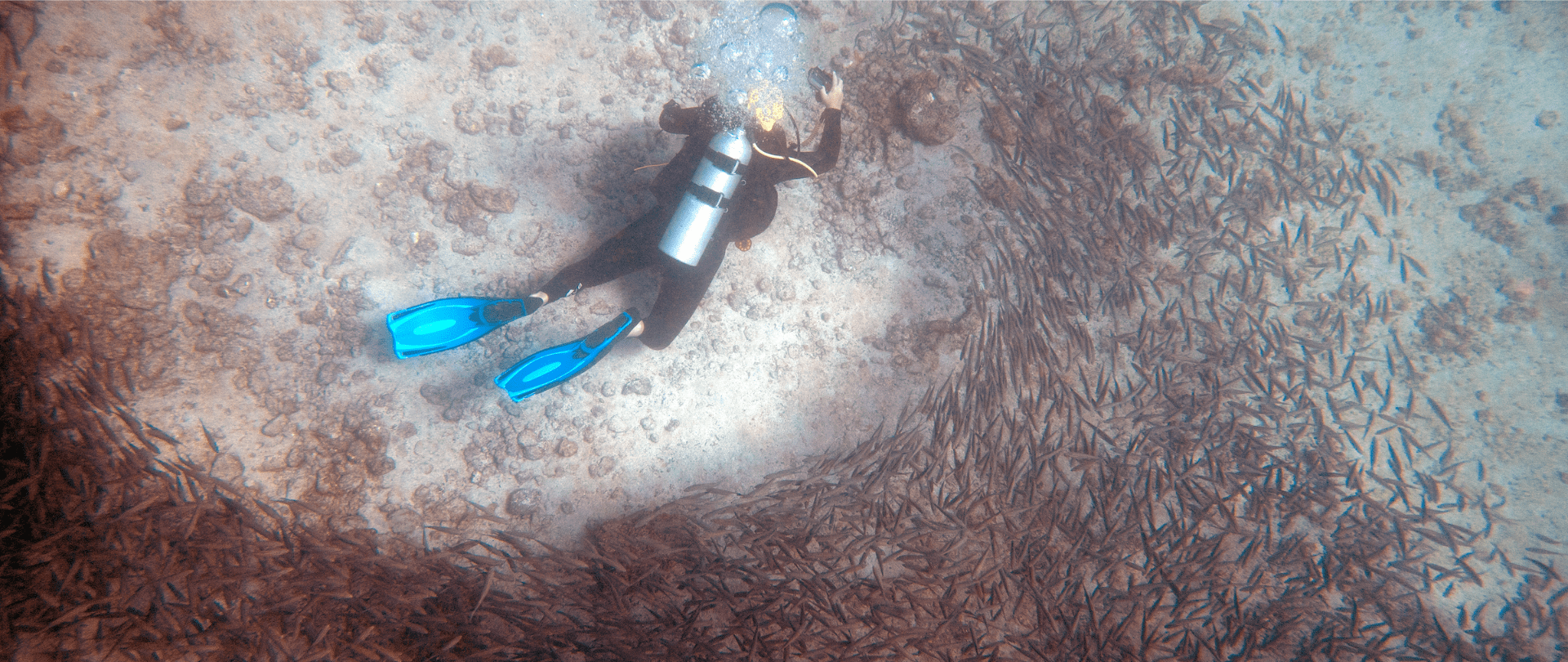

Removing invasive species is the essential first step towards restoring this ecosystem to full health, bringing back the abundance of species that connect the deep ocean and islands, and by doing so improving the resilience of the atoll to a changing climate.

Back at camp, dinner was always a highlight. Local ladies Tonaj and Helsina worked wonders for us with limited ingredients and there was plenty of good grub including mouth-watering local delicacies such as young coconut soup, salted parrotfish, giant pandanus and Marshallese doughnuts. In the evening a ukulele was passed around (it seems that everybody in the Marshall Islands plays ukulele like a professional), and the tropical night was filled with harmony as the locals played an extensive repertoire of very catchy Marshallese folk songs.

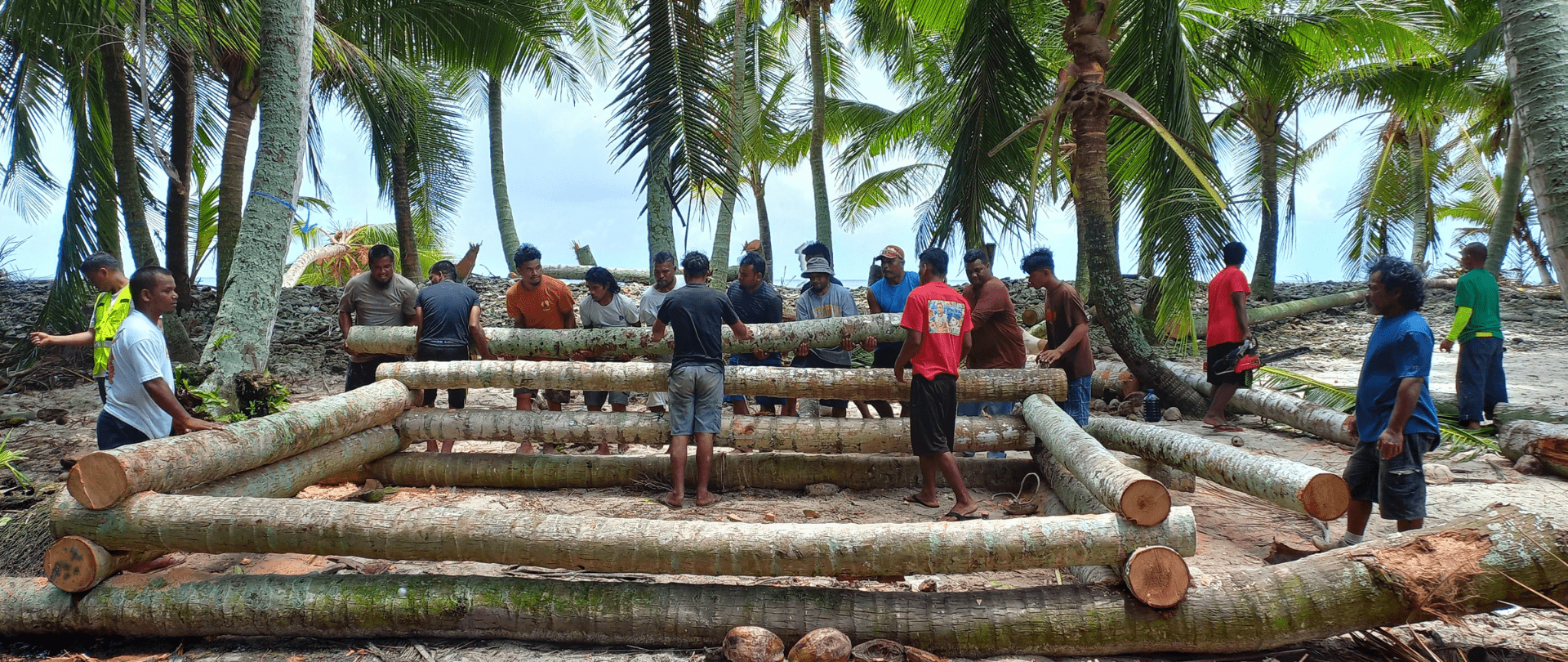

After three grueling weeks we had worked our way around the atoll and there were whoops of delight as we marked out the last lines on the furthest islet. We now had one more job to complete before we could begin baiting – the domestic animals belonging to the local community had to be rounded up and penned to prevent them from eating the bait. Thanks to the ingenuity and carpentry skills of the local community, this problem was quickly solved by felling some old coconut trees that were past their best and using the trunks to create “log-cabin” style pig pens. Chicken pens were constructed too, before the team fanned out into the forest and spent a full day herding the normally free-range animals into their new homes, where they would remain until the bait had broken down.

After the hard labor of cutting and marking the lines, the baiting seemed easy, and after only four and a half days I emerged from the forest on the last islet and flopped down onto the beach next to my comrades.

We were a tired but happy band – a lot of hard work had gone into this and despite the heat and the hardship we had achieved what we had set out to do – and no-one had been hit by a falling coconut, thank goodness.

We had done our very best and we could only hope now that we had been successful in removing every last rat. We will wait a year before a small team returns to monitor and confirm the success of the operation. In the meantime, the local community will be vigilant for any sign of rodents, especially in vessels and equipment coming from the neighboring atoll of Mili.

I hope that in the coming years the local people of Nadikdik get to enjoy the fruits of our labor – the pandanus, coconut, banana and papaya, no longer decimated by rats, and that the tropical night will not only be filled by the sounds of ukulele and human song, but also by the haunting cries of returning seabirds.

These eradication activities are part of the Regional Predator Free Pacific programme, within the Pacific Regional Invasive Species Management Support Service (PRISMSS) of which Island Conservation is a technical lead. The activities are funded under the GEF 6 Regional Invasive Project (GEF 6 RIP), which aims to develop and implement comprehensive national and regional invasive species management frameworks that help to reduce the threats from invasive species to terrestrial, freshwater, and marine biodiversity in the Pacific. The GEF 6 RIP is funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), implemented by the United Nations Environment Programme, and executed by SPREP.

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Mona Island, Puerto Rico is a key nesting ground for endangered species--but it's in danger! Read about our project to protect this beautiful, biodiverse island.

Read Coral Wolf's interview about the thrilling news of rare birds nesting on Kamaka

Audubon's Shearwaters are nesting on Desecheo Island for the first time ever! Read about how we used social attraction to bring them home.

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!

A recent monitoring trip to Late Island shows promising results!

Part 1 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!