The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

September 6, 2017

Written by

Emily Heber

Photo credit

Emily Heber

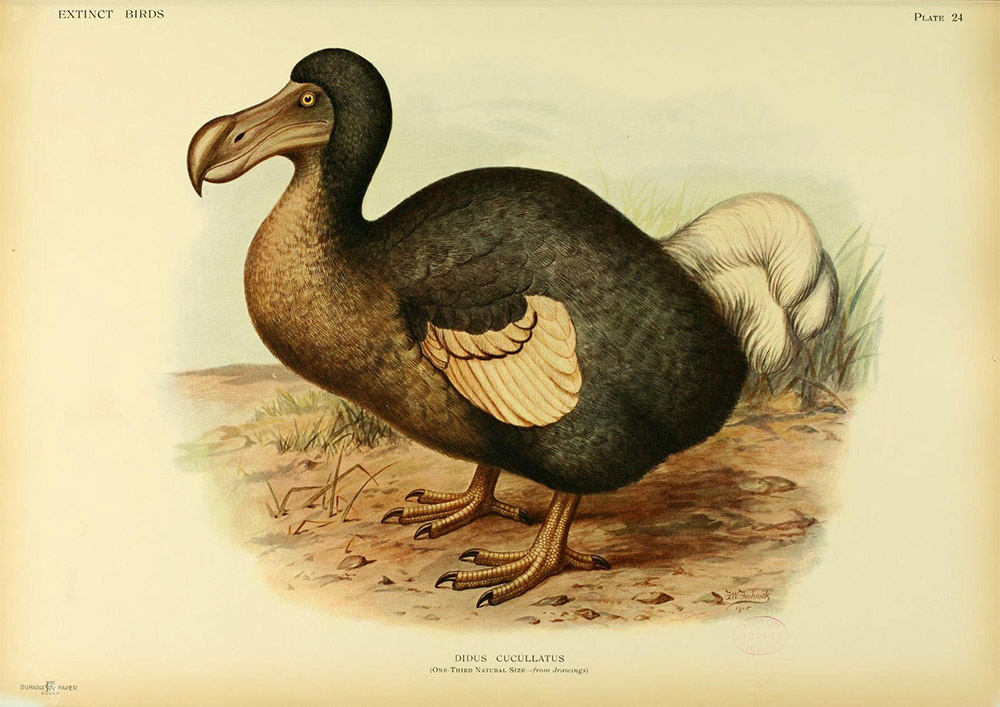

Mauritius Island was once home to one of the world’s most famous extinct species–the Dodo. The large grey bird was last seen in 1662, but researchers are still learning about the species and exactly how it lived on the island.

Researchers have long known that the Dodo bird was a fruit-eating bird related to pigeons and was largely responsible for seed dispersal for native plant species.

Their ultimate demise on the island was due to a combination of hunting and the introduction of invasive monkeys, deer, pigs, and rats. Dodo birds evolved on Mauritius without any natural predators, so when ships brought non-native species, whether intentionally or not, the birds had no evolutionary response for predation and competition for food.

Now researchers are studying what the bird’s life was like before the introduction of predators by studying the species’ growth patterns from preserved bones. Using the limited remainders of bones, researchers have begun to understand the life history of the mysterious bird. Dr. Delphine Angst of the University of Cape Town, South Africa commented:

It’s difficult to know what was the real impact of humans was if we don’t know the ecology of this bird and the ecology of the Mauritius Island at this time.

The new researcher revealed that Dodo chicks hatched in August and grew quickly into their adult forms out of necessity for survival before cyclone season in November to March. Although they grew to full size, researchers believe the species took years to reach sexual maturity.

Understanding how the species lived before invasive species and humans is crucial to understanding their evolution, explains Dr. Angst:

So that’s one step to understand the ecology of these birds and the global ecosystem of Mauritius and to say, ‘Okay, when the humans arrived what exactly did they do wrong and why did these birds became extinct so quickly?’

Clarifying the natural history of the large Dodo will clarify the impacts humans and invasive predators. Finally, researchers would understand how these threats drove a population from thriving to extinct in a mere century.

Featured Photo: Skeleton of a Dodo. Credit: Megan Danner

Source: BBC

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…

Island Conservation accepts cryptocurrency donations. Make an impact using your digital wallet today!

For Immediate Release Conservation powerhouse BirdLife South Africa has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC) – a global initiative aiming to restore, rewild and protect islands, oceans and communities – to support its work to save internationally significant albatross populations…