New Tech for Island Restoration: Sentinel Camera Traps

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

November 23, 2016

Written by

Sara

Photo credit

Sara

The Line Islands are positioned approximately 1,000 miles south of Hawaii, which also serves as the nearest land mass. With notable contrast to the surrounding barren open ocean, the modest sprinkling of isolated atolls is bursting with life. Though remote, the islands and atolls are not untouched. Human influence has reached these tiny breaths of land buffered by the ocean, and not without ecological consequence.

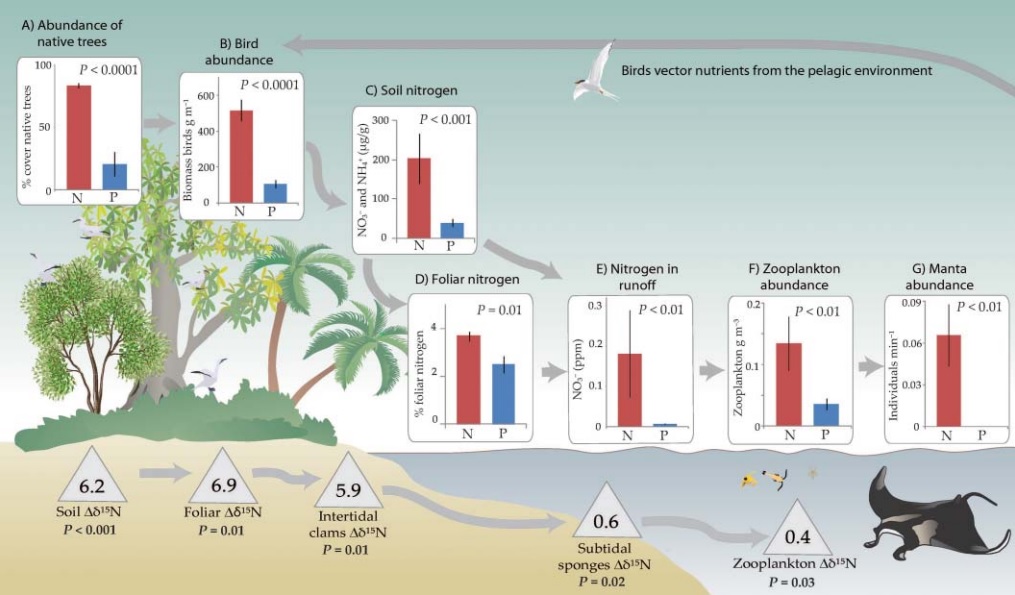

It turns out that scientists have been able to identify key differences between cultivated islands and less-touched islands. A study published in Scientific Reports brings new understandings of the complex ecosystem interactions that take place between land and sea.

The Land and The Sea: What’s the Connection?

Native trees on the Line Islands are “branchy”–they have a complex structure that provides the perfect place for nesting seabirds to roost. Inevitably, seabird droppings fall from the perches to the ground below, an occurrence which might not seem particularly interesting at first, but actually, during this process something very important is deposited into the earth: nitrogen. Nitrogen is a chemical element and essential nutrient for plants. Guano (bird droppings) fertilizes the soil underneath the branchy native trees. The nitrogen in the guano contributes to the health and growth of native vegetation.

Some, but not all of the nitrogen, cycles back into the native vegetation. Some is also carried by water to the island’s edges and into the ocean. The addition of nitrogen to the surrounding waters fuels the growth of phytoplankton–microscopic, photosynthesizing organisms found at ocean and freshwater surfaces. The phytoplankton are important for a number of reasons, but in the Line Islands they have a special role: providing food for Giant Manta Rays. Giant Manta Rays swim along the shorelines of the islands, feeding on the phytoplankton–the one and only item on their menu.

In addition to keeping Giant Manta Rays satiated, phytoplankton comprises the base of aquatic ecosystem functionality. Phytoplankton feed a variety of fish species, which the seabirds in turn eat. The seabirds, nourished by fish, roost in the trees, excrete waste, and perpetuate the nutrient cycle. The researchers determined that this series of connections “defines one of the longest ecological interaction chains yet observed in nature.” The cycle entails a transition of biological materials from land, to sea, back to land, and so on.

The study points out:

This interaction presents an interesting route through which oceans affect change on land, and changes on land can feed back to influence ecological processes in the oceans.

Remove One Link, and the Chain Will Break

Some of the Line Islands have been cultivated by people. As a result of this, native vegetation has been replaced with non-native palm trees. Giant Manta Rays found less frequently near these islands that have been impacted by humans. A closer look reveals that the phytoplankton they depend on for food are not available around islands dominated by palm trees. The researchers were puzzled. What do non-native palm trees have to do with Giant Manta Rays?

Careful observation revealed that seabirds avoid roosting in the non-native palm trees–and for good reason. Palm trees do not offer the ideal roosting structures that the native vegetation does. Palm trees lack sturdy branches, and they toss about in windy conditions. Seabirds steer clear of the islands and atolls covered in palms, meaning that the soil is deprived of guano, its primary source of nitrogen. Without nitrogen in the soil, there can’t be nitrogen runoff into the sea. Thus, the waters surrounding cultivated islands are oddly quiet, harboring nowhere near the numbers of phytoplankton and Giant Manta Rays that nearby undisturbed islands do.

Another ecological disturbance that can break the chain of interactions is the presence of invasive species. By preying directly on native birds that act as seed-dispersers, invasive rats can impede the growth of native vegetation, as has been documented on Palmyra Atoll. Island Conservation conducted a restoration project on Palmyra with The Nature Conservancy and The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2011. After removing the invasive rats, native Pisonia plants flourished and wildlife populations are steadily recovering.

How can this knowledge help us to restore and protect island ecosystems?

Understanding the linkages between terrestrial and marine island environments empowers us to take specific, informed conservation actions. At the same time, the recognition of the ecological connectivity between land and sea invites conservationists that may have previously bound themselves to one environment to broaden the scope of their projects and expand their visions for restoration.

Additionally, these findings sound a warning for those who modify remote island ecosystems, whether through cultivation, development, recreation, or otherwise. These ecological systems are held together by natural linkages that have formed over millennia. We have the power to rapidly dissolve those interactions. In the case of the Line Islands, we have arrived at a good understanding of how land and sea are linked. Our newfound ecological awareness can guide our actions and help us to make environmentally responsible decisions.

The knowledge that terrestrial and marine island ecosystems are linked elevates the importance of terrestrial island conservation efforts. Projects to correct ecosystem disturbances, such as invasive species removal, benefits not only the island itself but also the surrounding marine environment.

Source: Scientific Reports

You can also read an account of this complex ecological chain at Environment360

Featured photo: Palmyra Atoll. Credit: Island Conservation

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…