Rat Eradication on Nukufetau Atoll Bolsters Pacific Conservation and Enhances Community Resilience

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Restoring islands for nature and people worldwide.

Published on

August 27, 2019

Written by

Wieteke Holthuijzen

Photo credit

Wieteke Holthuijzen

Oceans cover more than 70% of the world’s surface area and are key to providing food for over 1 billion people and supporting the livelihoods of an additional 200 million people. Yet, our knowledge and understanding of our marine environments lacks; more than 80% of the ocean is unmapped, unobserved, and unexplored. In some areas of our world’s oceans, seawater columns depths plunge down to more than 10 kilometers, a distance far beyond reach. But not for seabirds including Midway’s Albatross.

Albatross, like many other seabird species, act as sentinels for sea—an indirect proxy for monitoring the health of oceans and studying marine ecosystem function. After all, these seabirds fly thousands of miles each year in search of food and spend the majority of their lives (upwards of 90%) at sea. Since albatross depend on finding their food in the open ocean, any changes in availability and location of their food sources can have a substantial impact on their health and reproductive success. Albatross also breed in the millions at Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge and display high nest site fidelity (meaning they nest in the same place from year to year), so they can easily be studied and monitored over time. As such, they are natural tracking devices of entire oceans. This is where seabird monitoring comes into play—this is why we collect data.

On Midway, we estimate Laysan and Black-footed Albatross’ populations and long-term viability by collecting information on reproductive success and survival. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service volunteers collect this data, which helps the federal agency to monitor population cycles in species (and be watchful of those at risk) and stay informed about the health of the ocean. Volunteers, like myself, collect data from seabirds from nest-building stage through chick fledging, tracking the fate of hundreds of individual nests, as well conducting population counts. This yields a yearly index of reproductive success (number of chicks successfully fledging per number of eggs laid). Ultimately, this gives us information about a very important question: how successful were the birds at producing chicks?

Reproductive success monitoring begins during the blustery winter months out on Midway Atoll. At this time, despite the wind and the rain, most of the albatross across Midway have recently laid eggs. Throughout Sand Island (Midway’s largest island), we monitor reproductive success at specific plots; within in each plot, we identify all albatross nests and keep track of each nest from freshly-laid egg to fledged chick through bi-weekly checks. Based on this data, we can get a rough idea of how many chicks survive and in turn what the long-term success “rate” is.

Each nesting albatross parent in a given plot is banded with both a unique, 9-digit stainless steel USGS band and a red-and-white auxiliary (“AUX”) band; these bands help us to keep track of individuals, as well as the reproductive success of specific breeding pairs. We try to decrease the amount of disturbance to these birds as much as possible and normally we use our “chick sticks” to gently nudge away the breeding parents’ feathers to check for their auxiliary band code. However, with the chick season readily approaching, we also take the time to check the status of the nest—in other words, gently pushing the breeding parent up to check whether there is an egg or downy chick tucked away safely!

Survival monitoring is quite similar, in that we only focus on the adults that return to specific survival plots each year. Albatross are quite philopatric (meaning that they come back to nest at the same spot, usually within a few meters, each year) so there’s a good chance we’ll come across long-time residents within a given plot. Not only does this data give us a sense of the adult survival (or more specifically, survival of returning adults) but it also gives insight into the frequency at which albatross breed (that is, if they breed every year or if they occasionally take a year off to molt or undertake any other energetically intense activities). While the percent of chicks that survive the initial treacherous trek out to sea or the survival rate from chick to breeding age are unknown, these basic data on reproductive success and adult survival give us valuable information and insight into long-term demographic trends.

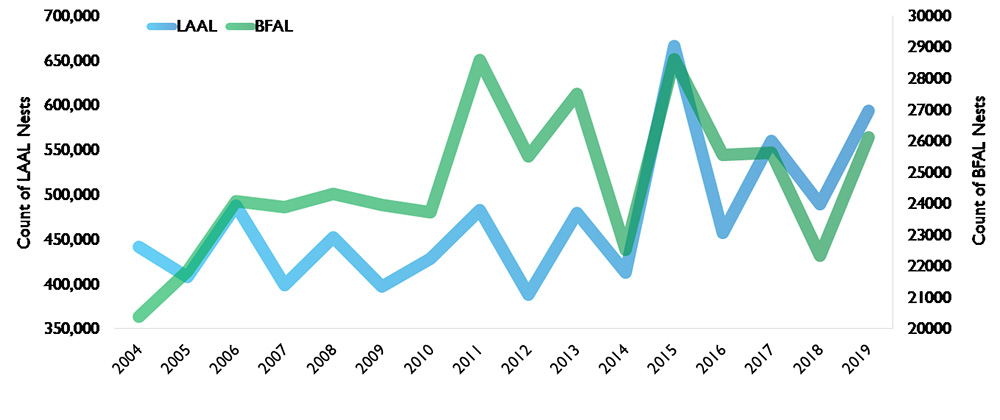

In addition to reproductive success and survival, volunteers also help with an atoll-wide census each winter—yes, every albatross is counted! Over the course of two weeks, teams of volunteers conduct transects (“sweeps”) across sectors of Midway’s three islands and count every Laysan and Black-footed Albatross with the aid of clicker-counters. This atoll-wide albatross census has taken place annually since 2004 and provides critical insight into the state of the albatross colony.

After work one day on Midway, I remember going to the beach and strolling around, looking out at the afternoon sunlight reflecting off of the choppy waves. Beyond the horizon, I knew that there are innumerable issues that awaited the albatross. Pelagic longlines under the waves, plastic bottlecaps floating along. In the simplest sense, it was overwhelming. At the same time though, oddly enough, being on Midway was an incredibly inspiring experience. With all the work that I did each day out here, I felt like at least I’m doing something, rather than twiddling my thumbs and worrying about the unreachable issues that I couldn’t address. I sat down and as I did so, a Laysan Albatross came waddling out from behind a native Naupaka (Scaevola taccada) shrub. I saw that is had an aluminum band on its left leg and I squinted, trying to read a few of the identification numbers on the band. It was heavily worn and the numbers had faded away. We stopped and gazed at each other for a few moments. Albatross are incredibly long-lived species and this particular bird could be the same age, maybe even older than me. I wonder what it had seen out at sea but then also marvelled at the triumph that this species is, to be alive and well despite the woes in the world.

Even though there are some threats that we can’t readily address from Midway (such as pelagic longlines and albatross bycatch mortality) we can focus on one thing: safe breeding habitat. Midway’s Albatross face a new threat—invasive, predatory mice. Island Conservation and our partners are going to remove them in July 2020 and restore the balance on the Atoll, but we need your help. Learn more out campaign to save Midway’s Albatross.

Featured photo: Laysan Albatross adult and chick. Credit: Tom Green/Island Conservation

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…

Island Conservation accepts cryptocurrency donations. Make an impact using your digital wallet today!

For Immediate Release Conservation powerhouse BirdLife South Africa has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC) – a global initiative aiming to restore, rewild and protect islands, oceans and communities – to support its work to save internationally significant albatross populations…

Video captures insights and hopes from the partners who are working to restore Lehua Island, Hawai’i. In 2021, Lehua Island officially became free from the threat of invasive rodents. This is a huge accomplishment that has enriched the region’s biodiversity…

Carolina Torres describes how the project to restore and rewild Floreana Island signals hope for a future where people and nature can thrive together in the Galápagos.