March 11, 2025

Press Release: New eDNA Tool Can Detect Invasive Rodents Within an Hour

New environmental DNA technology can help protect vulnerable island ecosystems from destructive invasive species.

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Our new online shop is live!

PRESS RELEASE

For release Nov. 8, 2022, 12 pm PST

Contact: Sally Esposito, Island Conservation, Interim Strategic Director of Communications, sally.esposito@islandconservation.org

Resources: Interviews, peer-reviewed publication, photos

Introduced, damaging, invasive rodents on islands are a leading cause of species extinctions globally. These interlopers eat endangered sea turtle and seabird eggs, hatchlings, and even adults. The loss of these and other key connector species can cause the entire land-sea ecosystems to collapse, destroying livelihoods, and health and food sources for many island communities and Indigenous Peoples who depend on these resources. Thousands of successful invasive species eradications on islands have demonstrated this intervention to be one of the most impactful conservation and restoration tools available to help restore and rewild island-marine ecosystems making them and their communities more resilient in the face of climate change and other stressors.

Researchers at University of Adelaide, Australia released findings today on potential gene drive technology to control invasive mice on islands. The researchers, associated with the Genetic Biocontrol of Invasive Rodents consortium (GBIRd), developed a world’s-first gene drive strategy, called t-CRISPR, that could potentially suppress or even eradicate an invasive mouse population from an island. Using sophisticated computer modeling performed by co-first author Dr. Aysegul Birand, the researchers predict that 250 gene-modified mice could eradicate an island population of 200,000 mice in 20 years. The results of the study were published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA.

The potential addition of targeted, species-specific tools in the island conservation toolbox, such as gene drives, would give many more island communities the option of removing invasive rodents. Using the methods available today, it is only feasible to restore about 15% of the world’s islands threatened by invasive species. Emerging genetic technologies promise to be more precise and humane and offer hope in aiding in invasive species eradications on islands where traditional interventions are not currently possible. New tools would contribute to increasing the scale, scope, and pace of interventions on islands, which will be priority sites for achieving the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework targets to be decided at COP15 in Montreal later this year.

“We are cautiously optimistic, but this breakthrough offers hope that we can turn the tide on the extinction crisis happening on islands,” said David Will, Head of Innovation for Island Conservation, a member of GBIRd. “Island communities, stakeholders, and their governments can now deliberately and collaboratively assess the first genetic technology with the potential to protect the hundreds of islands currently beyond our reach.”

GBIRd is a group of diverse experts from six world-renowned universities, government, and not-for-profit organizations exploring genetic tools to scale up efforts to protect island communities and prevent island species extinctions.

“This is the first time that a new genetic tool has been identified to suppress invasive mouse populations,” said GBIRd member and lead researcher Professor Paul Thomas from the University of Adelaide, and the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI). “The t-CRISPR approach combines a naturally occurring gene drive with cutting-edge DNA editing technology to alter a fertility gene and progressively impact the population’s ability to reproduce.”

Other scientists have engineered mosquitoes with gene drives that stop the parasite behind malaria and are working on gene drives to eradicate the mosquitoes that spread dengue, chikungunya, and Zika.

“Up until now, this technology has been aimed at insects to try and limit the spread of malaria,” said post-graduate student Luke Gierus, a co-first author of the research paper. “The use of t-CRISPR technology could provide a humane approach to controlling invasive mice on islands. We are also working on strategies to prevent failed eradication due to the emergence of gene drive resistance in the target population.”

While Thomas and his lab have spent years developing this novel mouse gene drive technology, his team has been working alongside other institutions in the GBIRd consortium to investigate other aspects including the social, ethical, and biological potential and risks of gene drive technology.

“Our broader project includes consideration of societal views and attitudes and is integral to our ongoing research relating to this gene drive,” Professor Thomas said.

“While t-CRISPSR has been designed to specifically target mice there is evidence that gene drives could be developed to target other invasive species that threaten island ecosystems,” said GBIRd member and co-author Dr. Owain Edwards, CSIRO Group Leader for Environmental Mitigation and Resilience. “As part of this research, the safety assessments for this technology are conducted according to the highest standards. Because this is the first prototype for a vertebrate gene drive, interested stakeholders will include many from the international community,”

The GBIRd consortium’s next steps to safely assess this technology will be conducted in line with the world’s leading gene drive research and public values alignment guidelines like these issued by the US Academy of Sciences.

“There is still much work to do to determine the efficacy and suitability of this technology in simulated real-world settings and to identify and integrate safety mechanisms to ensure this technology is safely self-limiting”, says co-author and GBIRd member Dr. Toni Piaggio from the US Department of Agriculture. Piaggio is also a lead researcher on how DNA unique to an island population, known as locally-fixed alleles, could be used to limit gene drives. “It will be at least another 5 to 10 years of focused research and consideration of societal views and attitudes before this technology can be evaluated for potential field trials in partnership with interested communities and stakeholders.”

Formalized nearly a decade ago, the GBIRd consortium now includes Island Conservation, North Carolina State University, Texas A&M University, US Department of Agriculture, Australia’s National Science Agency CSIRO, University of Adelaide, and affiliate members such as the Center for Invasive Species Solutions, and Macquarie University. The research was supported by the South Australian Government and NSW Government.

###

Resources:

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Publication

University of Adelaide Press Release

Contact:

Sally Esposito, Island Conservation, Interim Strategic Director of Communications, sally.esposito@islandconservation.org

Professor Paul Thomas, School of Biomedicine, The University of Adelaide. Mobile: +61 (0)449 898 765. Email: paul.thomas@adelaide.edu.au

Lee Gaskin, Senior Media and Communications Officer, The University of Adelaide. Mobile: +61 (0)415 747 075. Email: lee.gaskin@adelaide.edu.au

Supplemental quotes:

Dr. David Threadgill from the Texas A&M Institute for Genome Sciences and Society, co-author on the study and GBIRd member:

“This research builds off nearly a decade of research into the t-allele, a naturally occurring gene drive in mice which shows a nearly 95% inheritance rate in wild populations. Having a range of gene drive strategies for society and communities to consider will be critically important and this is likely the first of many.”

Background information:

Ethics and Decision-making

Why Islands

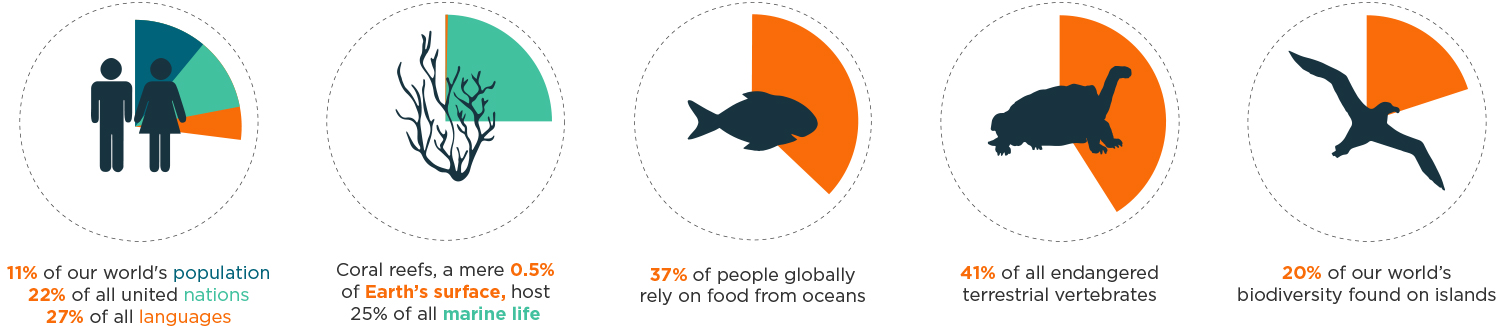

Islands-marine ecosystems are host to some of the highest concentrations of plant, animal, and human diversity. Islands and oceans are essential to:

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications