The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

April 23, 2018

Written by

Island Conservation

Photo credit

Island Conservation

By: María Victoria Coutts

Efforts to remove invasive rabbits that plagued the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve, Chile, have been declared successful, meaning today, the region’s native seabirds have a chance to recover. One of the main characters of this mission was a friendly dog named Finn.

His first great mission: a desert island

Finn is a 10-year-old Labrador retriever who was born in New Zealand and was rescued from a kennel. For the next few years of his life, Finn was specially trained to find rabbits.

First he worked for the Tasmanian Parks and Wildlife Service and later on embarked on a trip to a desert island in Australia: Macquarie Island. There, along with a team of biologists from Island Conservation, an organization dedicated to preventing extinctions by removing invasive species from islands, he carried out his first major mission.

In Australia, Finn became a key part of the island’s Pest Eradication Project. Finn and other specialist dogs worked hard for three years to detect European invasive rabbits (the common rabbit we all know) that in 1879 had been introduced as a food source, but after some time, had turned into the perpetrators of the almost catastrophic destruction of the vegetation on the island. The project was declared a success in 2014, and currently, the site is free from invasive rabbits, rats, and mice.

But Finn barely had time to rest before he was called for a new mission.

Rabbits invade an island in Chile!

This time, the adventure was in a country that needed Finn urgently. He could not refuse this opportunity to protect native wildlife, and in 2014 he arrived in Chile from Australia, along with his trainer and faithful companion, Karen Andrew.

The Humboldt Penguin National Reserve, located partly in the Atacama and Coquimbo regions, was in danger. European Rabbits had been introduced to the islands of Choros and Chañaral in the beginning of the 20th century so they could have a source of animal protein. Richard Torres, manager of protected wild areas at CONAF, explained:

It is a story that has happened on many islands around the world, where sailors or fishermen did this in order to have food in isolated places. However, these species, because they are not part of the island ecosystem, cause harm to the native biodiversity.

The problem was that these rabbits, completely harmless to the naked eye, began to destroy the native bushes and herbaceous plant and occupied the nests of Peruvian Diving-petrels and Humboldt Penguins. Plus, they devoured the cactus that gave shade and shelter to the Humboldt Penguins’ chicks. In short, the rabbits became true enemies and destroyers of the place (poor fellows, they did not mean to, but they left behind a great mess!). Torres said:

Penguins, for example, are species that have one partner and a nest. The rabbits, by taking their nests, would force them to look for new places to nest, which requires a lot of effort and time; this could cost them an entire reproductive cycle, which only happens once a year.

In 2009, when faced with this not-very-encouraging panorama, the project of Ecological Restoration of the Humboldt National Penguin Reserve began, which in total lasted nine years. So what did they do about the rabbits?

The work consisted of removing the invasive species from the islands where the Humboldt Penguins and Peruvian Diving-petrels nest, explains Torres.

For this, in coordination with Island Conservation, they applied a conservation bait product similar to those commonly used in agriculture to Choros Island. The product would end the rabbits’ legacy of damage and finally, the native birds would recover their homes and habitat on the island.

Finn in action

Next, the team needed the help of a dog to confirm that they had definitively eliminated the rabbits, as a dog’s nose can detect any remaining individuals. That was how in 2014 Finn arrived on the island of Choros; for three weeks he searched from top to bottom looking for possible traces of rabbits, his specialty.

When Finn finds a trace of invasive species, he is rewarded by his trainer with affection, games or food. It is a demanding level of training, since in the field there are many distractions, but he was focused and prepared not to pursue native species such as penguins. Luckily, on Choros, Finn detected no invasive rabbits!

Once it was confirmed that there were no rabbits on Choros Island, Finn had to return to Australia. However, the transfer would have been very expensive because of strict biosecurity barriers (that is, Finn had to undergo expensive exams to be able to return to his native land). It was then decided to make Chile his new home, because he was already at a stage in his life to be declared a senior or “retiree.” Bringing him back to Australia did not make much sense, explains Christian Lopez, a member of Island Conservation who ended up adopting Finn.

In 2015 Finn went to help with another conservation project in Juan Fernández, and in 2016 he returned to Chañaral Island in the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve to confirm that they had removed the invasive rabbits. This island is bigger and the terrain more complex than Choros; the work there was a bit more difficult, but at the end of 2017, an operation that lasted five weeks was successfully completed.

A hero with a wet nose

Finn’s role in the project was crucial; thanks to his help, conservationists were able to confirm the work they had done on the islands was a success, according to Island Conservation.

With the limited senses of sight, hearing, and smell we human beings have, we need a lot of time to cover the island again and again to be certain that there are no invading rabbits left. “The sense of smell of a sniffing dog allows us to cover much more land in less time.”

Torres tells us that the Choros and Chañaral Islands play a key role in the survival of Humboldt Penguins and Peruvian Diving-petrels, because these regions comprise the best nesting sites for these birds globally. “This is a milestone in global conservation,” he says.

The results?

Simply amazing! For the first time in 100 years, there is hope for the threatened birds to live in peace thanks to the elimination of the invasive rabbits.

“The first island (Choros) was free from invaisve rabbits in mid-2014. Consequently, it has had more time to show signs of improvement. On this island, after the removal of the invasive rabbits, the vegetation cover has significantly increased, and the number of nesting seabirds has also increased. In the case of Chañaral, whose success was achieved in late 2017, an increase in plant cover has been recorded, and we have had a great discovery: the identification of 17 plant species never before described,” says Torres.

But what happened to Finn?

After finishing in Chañaral, he returned to the Juan Fernández Archipelago, where he became a superhero inspiring responsible pet ownership. On the island, his trainer has taken him to activities with children within the community, where he has demonstrated his skills as a trained dog to encourage children to adopt and treat pets well.

Now Finn is retired and enjoying life, like an ordinary dog, on Robinson Crusoe Island in the Juan Fernández Archipelago.

Meet the real face of Finn!

Originally published by El Definido

Leer en Español/Read in Spanish

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

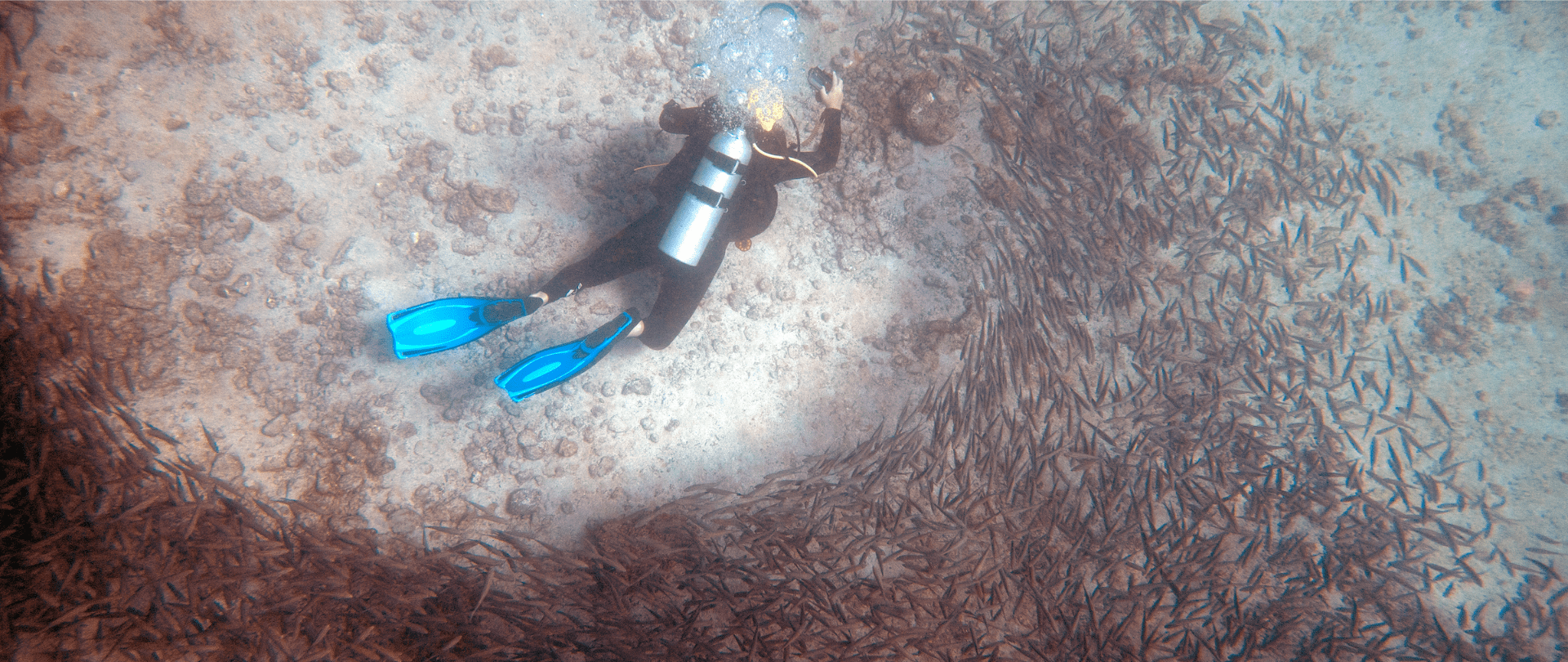

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!