October 29, 2025

Data Shows Endangered Palau Ground Doves Swiftly Recovering After Successful Palauan Island Conservation Effort

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

Published on

October 3, 2017

Written by

Emily Heber

Photo credit

Emily Heber

By: Emily Heber

Animal behavior can often reveal something about the evolution of communication. Humans are scratching away at the surface of animal communication, conducting studies to better understand what other species are saying. A new study sheds some light on communications between Commune Murre mate pairs.

Scientists recently observed Common Murre pairs using behavioral cues to communicate their health status to each other. In a recent study published in The Auk: Ornithological Advances researchers observed the interactions between Common Murre pairs to find a connection between behavior and health.

The Common Murre (Uria aalge) is a seabird that lives in large groups called colonies and are found throughout the world. Murres are noted for bi-parental care of offspring, which means both parents play a role in rearing the chick and must cooperate and communicate effectively with each other. Researchers wanted to know how individuals within a pair communicate their overall health to each other.

A past study found that if Common Murres were equipped with geologgers, which were used to track their movements, they experienced prolonged and irregular turn-taking habits. The geologgers appeared to decrease the birds’ health, which sparked a question for Linda Takahashi, Anne Storey, Sabina Wilhelm and Carolyn Walsh, the researchers on the recent paper titled “Turn-taking ceremonies in a colonial seabird: Does behavioral variation signal individual condition?”. Do Common Murre pairs communicate their health to each other?

Typically, one Murre parent stays at the nest while the other forages for itself and its chick. To transition between nesting and foraging, Murres perform turn-taking ceremonies. Researchers had previously observed that sometimes the after approaching its mate, the foraging bird will not take over brooding at the nest but will instead return to the ocean to forage again, leaving the other parent to continue to incubate the egg. Why would the responsibility trade-off sometimes not take place?

Researchers were particularly interested in variations of the turn-taking behaviors, length of the ceremony, reciprocity, timing of a behavior called allopreening, and why pairs sometimes do not trade roles. Changes in these behaviors could be communications about health and negotiations of responsibilities between the pair. The importance of long term pair bond in survival suggests that these exchanges are crucial for successful reproduction.

The study analyzed the turn-taking behavior of the sixteen Common Murre pairs. The birds were evaluated for body mass and a level of Betahydroxybutyrate, a hormone that indicates ongoing loss of body mass. A high level of Betahydroxybutyrate would indicate prolonged weight loss — a clear sign that the bird is not healthy.

Researchers hypothesized that negotiations between pairs are aspects of cooperation and conflict that would give their partner a cue to their condition. Since both parents are invested in the health of offspring their communications must involve aspects of working together as well as protecting themselves. So how do Murres communicate?

Allopreening is a pair bonding activity during which birds clean each other’s feathers. A sign of cooperation, allopreening is considered to be an important social behavior, especially between parental pairs. Researchers found that long turn-taking ceremonies were correlated with poor body condition for one of the birds and a delay in allopreening between the pair. A delay in allopreening suggests a negotiation between pairs. A brooder would stall or prevent turn-taking by not allopreening their mate. A forager that returned without a fish began allopreening their mate at a higher rate than those that returned with a fish for the offspring. These variations in the timing of allopreening are one example of the process of negotiations and how the species communicates their health to their mate.

Bill fencing is a behavior seen in many bird species. In bill fencing, the birds use their bills to fight; it suggests escalating aggression between a pair and is a sign of conflict. Since foraging is more energetically costly than brooding, a less healthy bird might not want to forage in order to preserve energy; after a few cycles. Bill fencing is one behavior researchers noticed when pairs were in conflict over foraging and brooding. This contrasted with allopreening which researchers understand to be a part of cooperation between the pair.

Murres nest on rocky shores and steep cliffs, and although these areas might be difficult to access for many predators, the birds’ strategic choices have not made the species immune to the pressures of invasive and introduced predators. In the 19th and 20th century the presence of invasive rats caused dramatic declines in Common Murre populations. Now, the species has recovered but is still vulnerable to human disturbances and changing water temperatures, which could alter food supplies. Continued research to understand the behaviors and needs of the species can inform the mission to prevent extinctions.

Better understanding communication dynamics could support early detection of warning signs within a population. Observing changes in turn-taking ceremonies might be the first clue that a population is in decline, information that empowers conservationists and researchers to step in before the species is under serious threat.

Featured Photo: A Common Murre pair. Credit: AdititheStargazer

Additional Source: All About Birds

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

October 29, 2025

Astounding evidence of recovery on Ulong Island in Palau after just one year!

August 28, 2025

A new paper reveals the benefits of holistic restoration on Australia's Lord Howe Island!

May 19, 2025

Read our position paper on The 3rd United Nations Ocean Conference (UNOC 3) to see why we're attending and what we aim to accomplish!

March 20, 2025

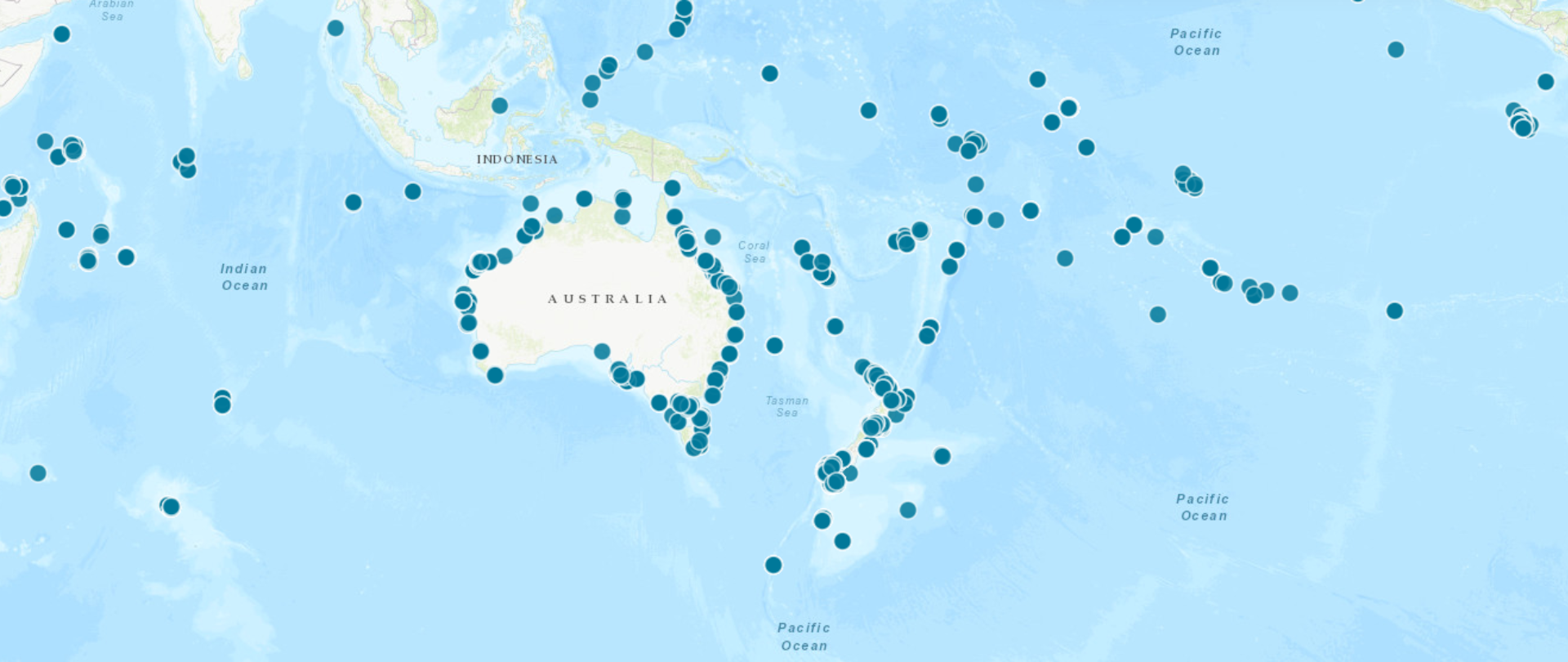

The DIISE is full of important, publicly-accessible data about projects to remove invasive species from islands all around the world!

December 10, 2024

We're using a cutting-edge new tool to sense and detect animals in remote locations. Find out how!

December 9, 2024

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

December 4, 2024

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

November 22, 2024

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

November 18, 2024

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

October 3, 2024

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!