The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

June 15, 2015

Written by

chad

Photo credit

chad

Tornados, earthquakes, tsunamis, hurricanes and, most recently in the Galápagos Islands, an erupting volcano; it’s clear natural disasters are not uncommon on our blue planet.

Add in the internet and 24-hour news programs, and we are instantly aware of everything that is going on from our own neighborhood to the most remote corners of Earth. Every time I see news of a phenomenon like these, I cringe while they report the devastation – regardless of the fact that I have never actually found myself directly in the epicenter.

For those of you like me who have not endured an event like this, do you consider yourself unexposed to a natural disaster? For a long time I did, until nearly 15 years ago when I bought a one-way plane ticket to the Galápagos Islands.

I was still a teenager earning a wildlife science degree at Oregon State when my advisor and friend Bruce Coblentz decided I needed to stretch my legs with something unique and appropriate to my skillset. He reached out to his colleagues and the next thing I knew I was packing my bags and leaving the country for Ecuador as a volunteer for the Charles Darwin Foundation, where I would be working with the Galápagos National Park to protect the famed Giant Tortoises by eradicating feral goats and donkeys from Santiago and Isabella Island (aka Project Isabela).

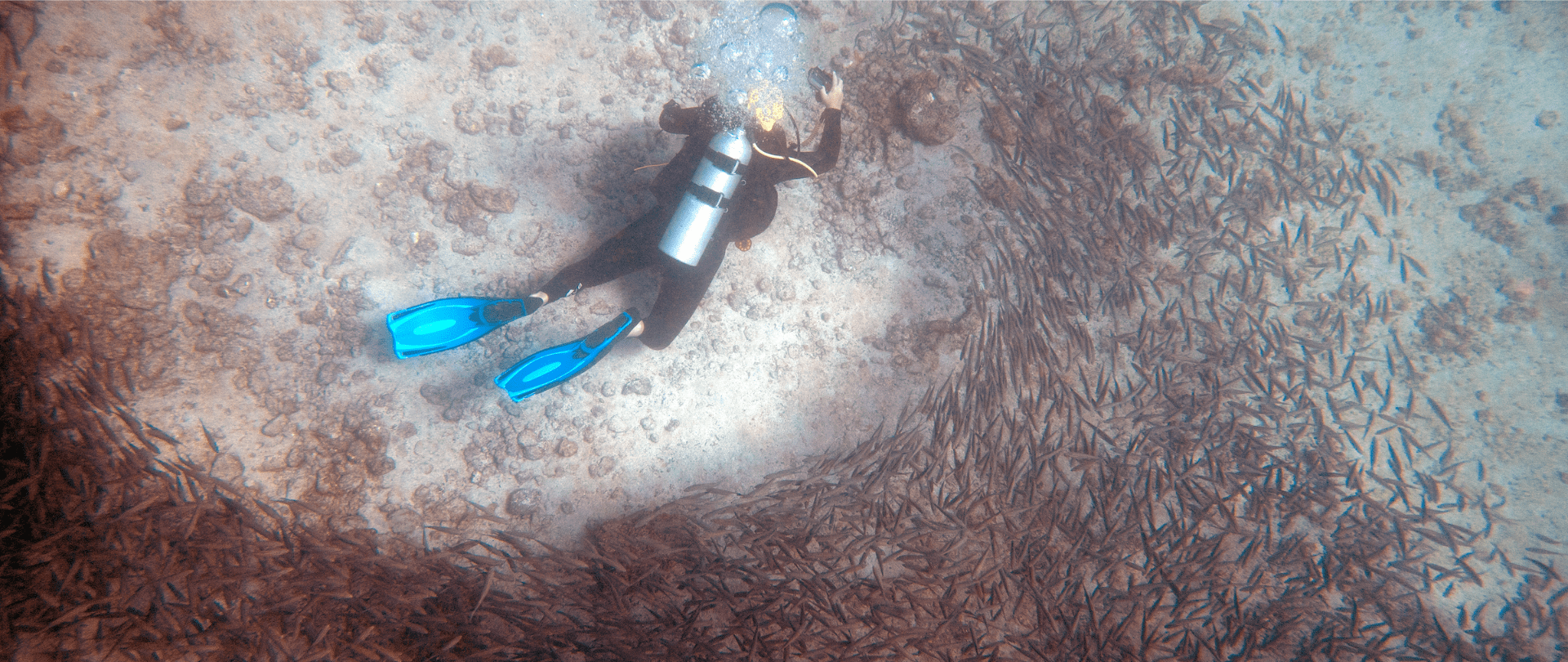

Eradicate? Feral? Huh? I was sure I’d figure out what that all meant later. In the meantime, I prepared a list of what I wanted to experience in this fabled land I’d heard so much about. First, I had to see a Giant Tortoise! Second, must swim with a school of Hammerhead Sharks. Third, observe one of Darwin’s famous finches in the wild. And lastly, enjoy a beer – legally. I arrived to the islands and soon made the acquaintance of an Aussie named Karl Campbell, who quickly replaced my list with two objectives: learn everything about Project Isabela and then implement my new-found knowledge.

I was soon up to speed and trudging through the vast landscape of Santiago Island in awe of what was in front of me. Pastures with boggy puddles, tortoises nearly the size of a Fiat treading mud, and deep trails draped over the island as if blanketed by a spider web.

“Wow! I am actually here in the Galápagos!” I said to myself while taking in a deep breath of fresh island air. What I didn’t know is that this wasn’t “the” Galápagos. Simply put, I was painfully naïve with my expectations. This landscape wasn’t even close to what Darwin and those before him witnessed. The pastures I was looking at were once forested, the mud bogs were previously refreshing ponds, and the wide and deeply scorn trails created by sharp ungulate hooves and incisors had paved over strategic tortoise tunnels through thick vegetation.

What I was witnessing was what my advisor Bruce coined “the living dead.” Many of the native and endemic species in front of me were set on course towards extinction – it was just a matter of time before they arrived at their destination. What was the cause of this? It was a ticking time-bomb that had been somewhat innocently placed there long ago without an understanding of the impacts.

Non-native invasive species, including pigs, goats, and donkeys, had been released by whalers, sailors, and pirates, and these animals simply did what they needed to do to survive; on Santiago and Isabella this meant devouring the landscape, which eroded the island to a state where vegetation struggled to regenerate and animals such as the Giant Tortoise were left to bake in their own shells under the equatorial sun. Other serious impacts took a trained eye to realize, such as mature stands of trees which were reaching the end of their reproductive lifespan without a single recruited sapling to show for over a century of existence.

As the project wore on, and the island’s dramatic recovery from systematically removing each and every ungulate on Santiago were apparent, I began to realize what a genuine natural disaster I was witness to. It became clear that although the impacts of invasive species weren’t instantaneous or sensational, such as an exploding volcano or rumbling earthquake, the islands and their irreplaceable species were at serious risk of being permanently destroyed right before our eyes.

This phenomenon is not unique to the Galápagos and is occurring on many of our world’s islands and their sensitive ecosystems. Fortunately, we can all do something about it. Unlike the natural disasters that strike in an instant, we are often able to identify and remove these ticking invasive species time-bombs with methods and strategies guided by science, improved awareness, and some old-fashioned hard work.

Looking back now, that first list of mine would have been simple to achieve, but that second list captured my attention and has kept me busy ever since. I’ve spent my career working to save species threatened by extinction due to the impacts of invasive species. Every day I know I’m helping prevent those preventable natural disasters.

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!