February 13, 2025

Biodiversity on Island Biomes

Islands are some of the most biodiverse places on the planet. Biodiversity, habitat diversity, and climate resilience are all linked together--click here to find out how!

We use cookies to help you navigate efficiently and perform certain functions. You will find detailed information about all cookies under each consent category below.

The cookies that are categorized as "Necessary" are stored on your browser as they are essential for enabling the basic functionalities of the site. ...

Necessary cookies are required to enable the basic features of this site, such as providing secure log-in or adjusting your consent preferences. These cookies do not store any personally identifiable data.

Functional cookies help perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collecting feedback, and other third-party features.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics such as the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with customized advertisements based on the pages you visited previously and to analyze the effectiveness of the ad campaigns.

Our new online shop is live!

Everything is connected. Atoll islands have often been deemed an inevitable lost cause when it comes to climate change and sea level rise due to their low-lying elevations. A new article in Cell Press aims to bust this myth as it ties atoll nations and Indigenous atoll cultures’ resilience to the Global North’s will to cut greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. A reduction in greenhouse gas emissions is essential, but there are local nature-based solutions that can complement the ever-growing need to significantly cut GHGs.

Don’t let their size fool you – there’s a lot at stake when we’re talking about the future of the 320+ atolls around the world. The ring-shaped island formations the remnants of extinct volcanoes where coral dynamic and growing island-coral reef habitats have grown and helped to deposit terrestrial substrate for life above water. Thus, atolls are home to extraordinary biodiversity with a myriad of seabirds, endangered marine turtles, and other key island species, as well as independent atoll nations and Indigenous atoll cultures. However, atoll islands have been a symbol for the loss of ecosystems to sea level rise, with atoll people being pinned as ‘environmental refugees’ – putting the finishing touches on this catastrophic picture that’s being painted. This narrative portrays atolls as a lost cause that are fated to disappear for good and assumes colonial behaviors where the Global North gets to decide when (and if) islands are inhabitable for Indigenous people.

Without a doubt, climate change is causing dramatic consequences for atoll islands. Sea level rise, increasing ocean temperatures, ocean acidification, increased and more frequent cyclones and storm surges, and marine heatwaves are all issues that atoll communities are facing regularly. But that doesn’t mean all atoll islands are a lost cause. Advances in geoscience, ecology, and conservation, along with Indigenous knowledge systems, can complement the move to reduce greenhouse gas emissions creating more hope for the future of atolls.

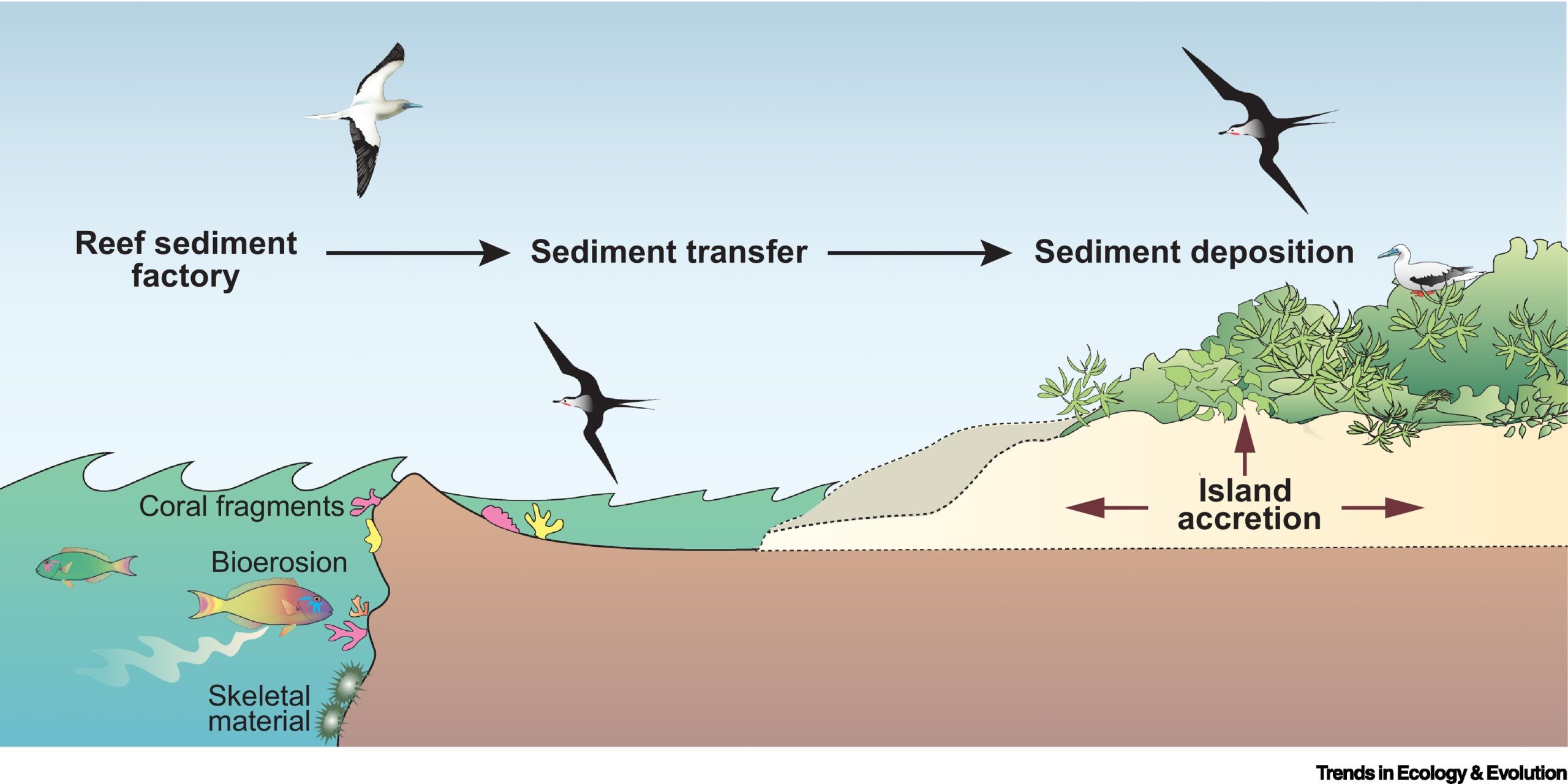

It may come as a surprise, but atoll islands are dynamic landforms capable of evolving to changing sea levels. In the article “Rethinking atoll futures: local resilience to global challenges”, the authors argue that “the key to unlocking nature-based solutions for building resilient atoll islands lies in the accretion processes through which atoll islands naturally adjust to changing sea levels and storm impacts.” This is more than a stop-gap measure, these nature-based solutions have long lasting positive impacts on these ecosystems. Accretion is the process where the atoll will experience sediment deposits from wind, waves, and the surrounding coral reefs. The maximum height of sediment transfer is dedicated mostly by things like wave height and water depth – so as sea levels rise, atolls can continuously evolve and increase in height.

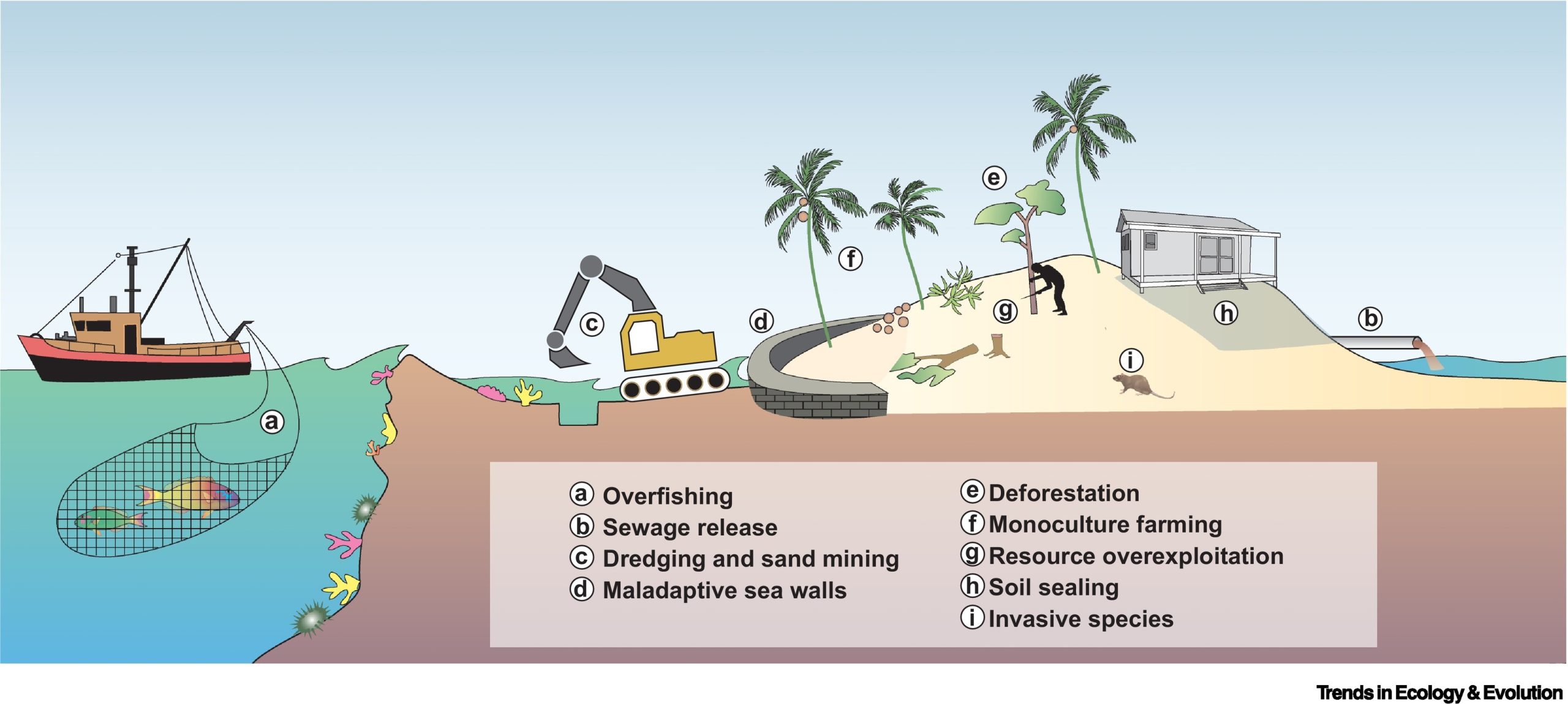

Humans have made modifications to atoll shorelines that influence the accretion process. Additions like sea walls disconnect the atoll islands from coral reef systems, which severely impact their ability to evolve in the face of the changing climate. This disconnection also influences the native vegetation on island, which then impacts the stability of the atoll. In some cases where atolls with native vegetation were hit with cyclones, the islands increased in height by up to 1.5m whereas atolls with a monoculture plantation of coconut palms eroded by up to 2.7m, some disappearing entirely. Other human-caused stressors to the accretion process aside from monoculture farming are things like overfishing, dredging, and of course, introduced, damaging invasive species.

How do invasive species impact atoll islands?

Healthy island-ocean ecosystems depend on a flow of nutrients in a process that connector species (like seabirds) help facilitate. Research shows that islands with robust seabird populations that feed in the open ocean and bring large quantities of nutrients to island ecosystems through guano deposits, are associated with larger fish populations, faster-growing coral reefs, and increased rates of coral recovery from climate change impacts. Atolls have a nutrient-poor soil, so guano deposits are able to enrich soil, groundwater, and plant communities.

However, many seabird species have been driven to local or global extinction (or near-extinction) due to invasive non-native predatory mammals, such as rats. By removing invasive species from the island ecosystems, connector species like seabirds are able to recover, thrive and contribute to the natural systems that are needed for atolls to adjust to the changing climate.

So what is the solution?

Rather than utilizing things like seawalls and dredging that typically disrupt these natural ecosystem functions , we need to look at local nature-based solutions that can restore the natural accretion process. Eradicating invasive species is a proven measure that vastly improves island ecosystems and communities. Accelerating the rate of seabird population recovery, or other rewildling interventions can further stimulate ecosystem recovery. Establishing marine protected areas can provide essential habitat for keystone bioeroder species like parrotfish, who contribute a large quantity of sand for the accretion process. We now need to take actions to amplify the multiple benefits of holistic island-marine restorations while we also conduct more research on how these nature-based interventions can translate to an improved accretion process.

Check out the original article in Trends in Ecology and Evolution >>

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Notifications