The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

November 27, 2019

Written by

Paula

Photo credit

Paula

The Galápagos Islands are famously known as the Enchanted Isles due to the treacherous currents and swirling mists that often cause the islands to disappear right in front of your eyes. During the colonial period, the Galápagos was sometimes considered a menacing and ominous place full of mystery. Several mysteries unfolded on Floreana, an island located in the southern end of the Archipelago with a history of love affairs and mysterious deaths—which continues to fascinate all who visit the island.

Today, Floreana is home to a community of 140 people as well as marvelous native and endemic fauna—although this island has lost more species than any other in Galápagos. Some of the unique species found on the island include the endemic Floreana Medium Tree-finch, the endemic Galápagos Petrel, and the Galápagos Short-eared Owl—the latter being the island’s only native predator.

Galápagos Short-eared Owls are considered a sub-endemic species of the Short-eared Owl found in other parts of the world. They are widely distributed among the Enchanted Isles, but the Floreana population possesses unique genetic traits not found in neighboring populations. Genetic population-level analyses have shown no evidence of owl movement from nearby Santa Cruz Island to Floreana Island, although the same analyses suggest that owl movement does occur in the opposite direction, from Floreana to Santa Cruz, but why this happens is unknown.

In addition to occasional long-distance travel to Santa Cruz Island (34 miles), prior to our study there were indications that Floreana owls may also travel to Isabela Island (around 43 miles) on the western side of the Archipelago (birds banded on Floreana later were observed on Isabela), adding uncertainty to the Floreana owl movement patterns.

To date, evidence suggesting these long-distance movements have come from banding and point count studies conducted on Floreana, where the number of owls sighted at different times of the year varies greatly (from two to 40 or more). This high fluctuation may result from owls leaving the island at certain times of year—perhaps due to changes in preferred prey availability. It is known that the owls feed on Galápagos Petrel chicks on Floreana Island, observational studies indicate that their population numbers appear to increase when petrels are breeding in the highlands and decrease during the months when petrels are absent.

As on most islands around the world, and within the Enchanted Isles of Galápagos, native and endemic fauna are not alone in paradise. Invasive mammals, such as mice, rats, and feral cats are also present on Floreana and negatively impact native and endemic fauna. The Galápagos National Park Directorate, with support from Island Conservation and other partners, is working to restore the island through the removal of these invasive species. This would allow the unique species of Floreana to recover and prepare the island for the reintroduction of some species that have disappeared from the island (e.g., the Floreana Giant tortoise, Mockingbird and snake species).

Before removing invasive rodents and feral cats from the island, risk to native species needed to be evaluated and managed. Therefore, in 2017 the Galápagos National Park, with support from Island Conservation and other scientists, determined that the population of Galápagos Short-eared Owls on Floreana would need to be placed in temporary captivity to minimize any risk from the operation. We also identified knowledge gaps associated with the owl’s ecology on the island that required additional research in order to implement this mitigation tactic.

In mid-2019, we worked to identify and resolve the movement patterns of Floreana Short-eared Owls to inform risk mitigation planning for the species during the rodent and feral cat eradication proposed for the island, and to recommend the best dates for trapping and placing owls in temporary captivity prior to the established implementation date for the eradication campaign. To obtain the required data, we walked for hours at night through vast open, often muddy areas, and through thick forests. We searched for Short-eared Owls to trap and fit with satellite transmitters utilizing a backpack fashion-like deployment.

Prior to our field work, we carried out extensive research to identify the appropriate equipment to deploy on the species, with careful consideration of their crepuscular (twilight) and nocturnal habits. The Short-eared Owls required small satellite transmitters, which are only available as solar-powered units. We also had to determine the most appropriate data transmission schedule to increase our chances of gathering the most accurate information while reducing the amount of power required to do so.

After our preparation and research, we successfully deployed four transmitters on four Short-eared Owls (females and males). The data transmitted shows fascinating movement patterns within the owl population. After deploying the transmitters in August and September, in early October one of the owls fitted with a satellite transmitter translocated itself to Isabela Island (data shows the bird spending time in an area between Cerro Azul and Sierra Negra volcanoes). So far, the other three have remained on Floreana.

We look forward to learning more from these owls and improving our understanding of their movement patterns. With this information, we will be able to develop the best protocols for ensuring the protection of this species during the invasive rodent and feral cat removal phase of this project to restore Floreana.

This article was originally published by the Galapagos Conservancy

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

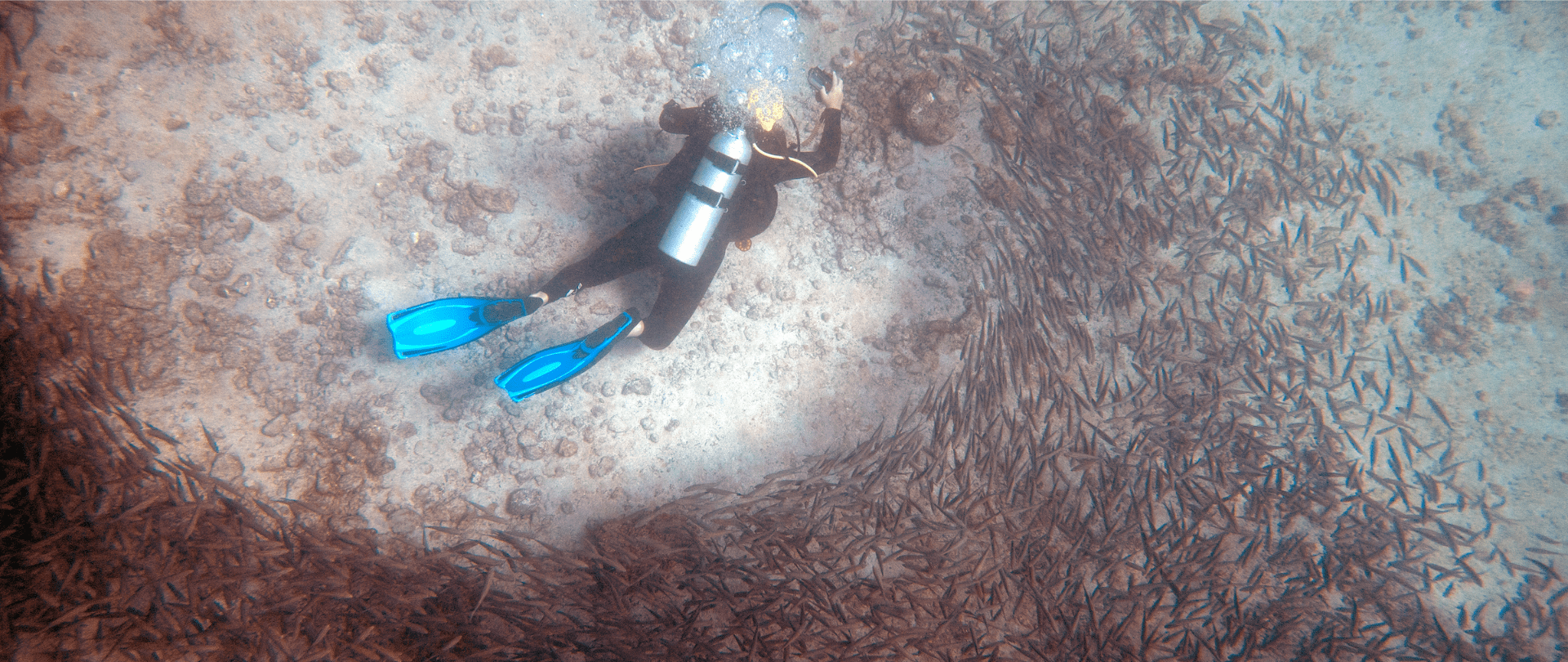

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!