The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

January 4, 2019

Written by

Island Conservation

Photo credit

Island Conservation

By: Ross Clark

Habitat restoration involves the removal of human landform changes and non-native plant and animal species that have led to a loss of natural habitats and native species. The process of restoration is often slow, challenged by the degree to which the environment has been modified, and often the end results are the enhancement of native species rather than the return of what used to be.

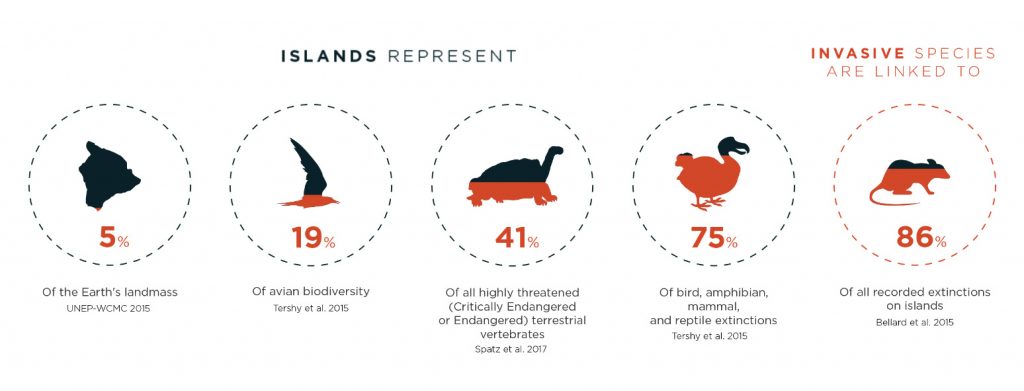

Island Conservation, a global habitat conservation organization headquartered in Santa Cruz has identified a unique strategy of working specifically on islands to successfully restore entire ecosystems. Islands make up 5 percent of the earth’s land mass but are home to 41 percent of endangered species and have experienced 75 percent of bird, mammal and amphibian extinctions. Sally Esposito with Island Conservation points out that the majority of extinctions happen on islands through the introduction of non-native mammals. Once introduced, these species run amok preying on island species that have previously been isolated from the competition. The new predators compromise rare and unique ecosystem dynamics that support the rare species. “Often the recovery of these island ecosystems” by removing introduced predators, “is like switching on a light” observes Esposito.

With the 19th and 20th century expansion of ocean travel, came the disembarkation of mammals to these islands. Rats along with cats, goats, pigs

Initiated in 1992 by UC Santa Cruz researchers working in Baja California, the program has expanded globally. Dr. Don Croll relates his early observations that islands infested by rats in the Sea of Cortez had less biological diversity and often lacked nesting birds. The removal of the pest led to the quick return of these birds.

Removal of rats from Anacapa Island off Santa Barbara similarly led to the successful return of nesting murrelets. On Palmyra, a remote island 1000 miles south of Hawaii, the removal of rats led to a documented 5,000 percent increase in recruitment of native forest vegetation. Previously, rats were eating the seed and seedlings of the forest. Now the expansion of forest vegetation is benefiting the seabirds which prefer the native plants. An added bonus for Palmyra was the loss of a non-native mosquito which had survived by feeding on the rat population.

In 2008 Island Conservation set up regional offices to work within the islands of the Galapagos, Chile, the Caribbean, Australia, and New Zealand. The team of more than 40 staff around the world works closely with local governments, foundations and landowners to devise eradication plans, implement the efforts and monitor success.

Staff has noted the incredible change these removal projects have on the plant and animal species of these islands. “The evidence is deafening” notes Esposito, “islands with rats are quiet while nearby rat-free islands are loud with life”. Recent research has documented that tropical islands free of rats also support healthy coral reefs, benefiting from nutrient-rich bird guano. The healthy reefs are more resistant to bleaching and support more abundant fish populations.

Efforts to build resilient populations of native species on islands, where they exist in isolation of human impacts, is also seen as an effective strategy to address global declines in species diversity posed by climate change. Island Conservation operates with the support of government grants, foundation support

This article was originally published in the Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Featured photo: View of Anacapa Island. Credit: Robert Schwemmer, CINMS, NOAA

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation attended the 16th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Join us in celebrating the most amazing sights from around the world by checking out these fantastic conservation photos!

Rare will support the effort to restore island-ocean ecosystems by engaging the Coastal 500 network of local leaders in safeguarding biodiversity (Arlington, VA, USA) Today, international conservation organization Rare announced it has joined the Island-Ocean Connection Challenge (IOCC), a global effort to…

Island Conservation accepts cryptocurrency donations. Make an impact using your digital wallet today!