The Ebiil Society: Champions of Palau

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

July 8, 2016

Written by

jose

Photo credit

jose

Cold water, rugged hikes, and swimming in vegetation.

By: José Luis Herrera

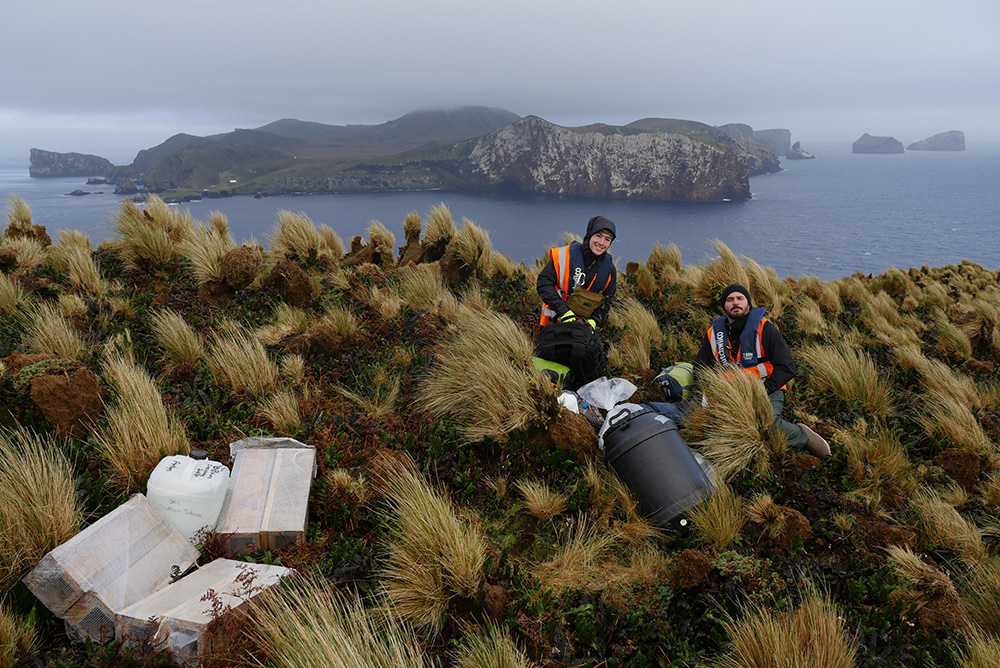

Antipodes Island, and its plant life, are rugged…to say the least. Some of that ruggedness is rubbing off on me, the hard way. I volunteered to be part of this two- to maybe five-month work deployment. I knew it was going to be a wild and remote place, but I definitely underestimated how challenging it would be simply to monitor the island’s plants and birds during this operation.

Day 1 on Antipodes Island, New Zealand – May 27, 2016

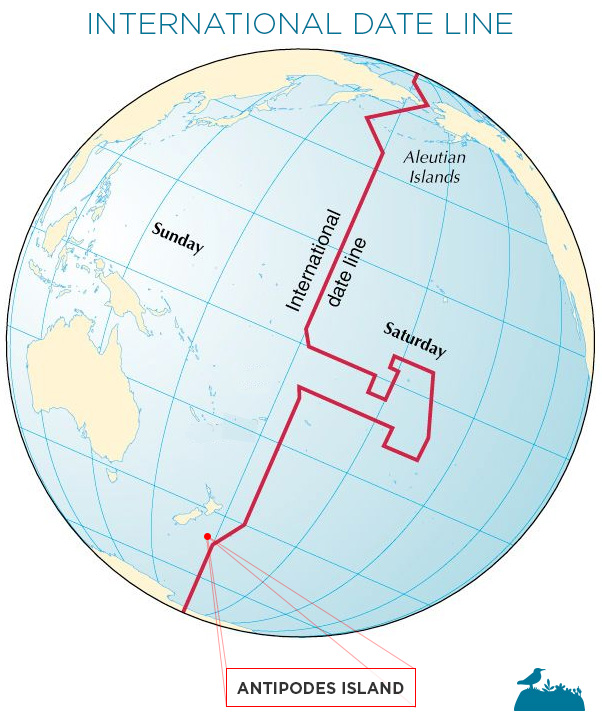

Situated just west of the international dateline about 600 miles south of New Zealand, Antipodes Island has no proper boat harbor. No docks. So, you may be wondering, “How do you get ashore?” A nice dip in the not-so-balmy South Pacific Ocean. You must jump from a small inflatable dingy into a rocky cove. You then hike up a cliff to the Biodiversity Hut, which is to be my home for the summer (well, actually the austral winter!).

It is during this short romp up the cliff that I make my first acquaintance with the hardy, sharp plant life that characterizes the New Zealand Subantarctic island region. My arrival to Antipodes Island was heralded not only by cold water but also by nicks and cuts! Who knew monitoring plants could be this painful?

In an attempt to avoid a fall while monitoring transects, I cut my hands grabbing these sharp leaf blades. Little did I know this was to become the daily ‘cost of doing business’.

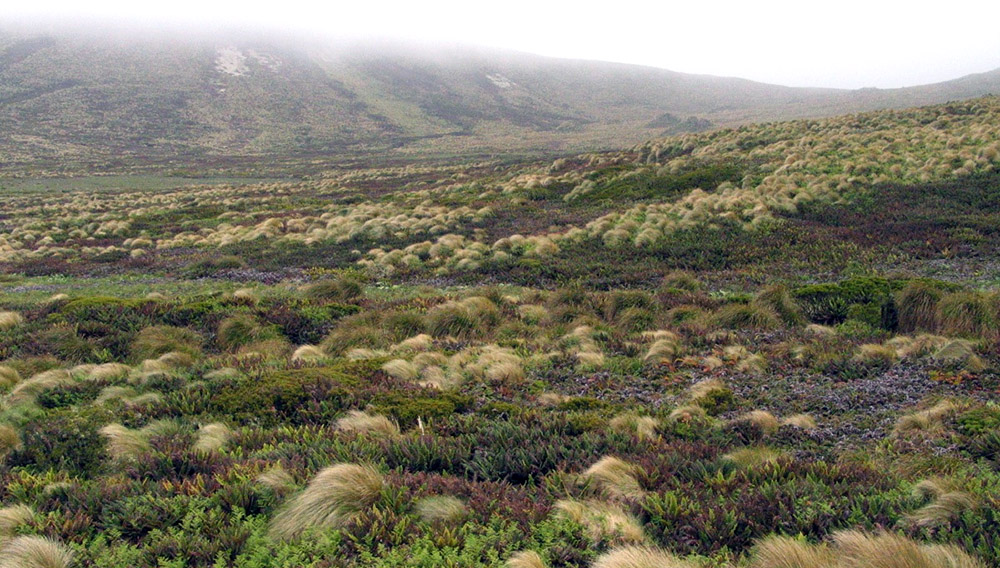

The landscape on Antipodes is dominated by a dense Coastal Tussock (bunchgrass) grassland comprised of Poa litorosa and a sedge Carex trifilda (a flowering plant that resembles some grasses). The latter is characterized by miniature ‘teeth’ along their leaf edge which are great at producing paper-cut-like lacerations. Unfortunately, this tiny observation was quickly made at the beginning of my first expedition across Antipodes. In an attempt to avoid a fall while monitoring transects, I cut my hands grabbing these sharp leaf blades. Little did I know this was to become the daily ‘cost of doing business’.

In the island’s interior, there is a mixture of grasses, herbs, bryophytes, shrubs, and ferns. The dense ferns and tussock grasses deserve particular mention because they conspire to become a most formidable duo, making the simple act of walking in a straight line an aspiration at best.

I decide to head out for a short walk our first day on the island. What looks like an inviting, level path is, in reality, a maze-like course of tussock pedestals that rises more than five feet above the ground. Their conspirators are thick walls of hardy fern stands and bunches of my new best friend the sedge, Carex trifilda. One minute I’m trekking happily across a mat of grass, and the next minute, I’m navigating out of a ‘grass canyon’ that rises above my head. It seems there are hidden gaps separating these individual tussocks “islands”.

I claw my way back to the surface (with a few new cuts courtesy of our friendly local sedges) and head for a dense stand of Shield Ferns (Polystichum vestitum) that should provide more stable footing, as they don’t seem to grow as tall as the challenging tussock islands. Alas, I am mistaken; with my next step, I’m tumbling head over heels into yet another hidden drop between the fern trunks and again I find myself quite literally swimming in vegetation.

Think of the miles here like you would dog years—one hike feels more like seven and can take just as long to complete.

After dozens of repeat performances like this, I decide I need to establish a more amenable working relationship with this new and challenging plant community. Despite being an experienced hiker, I need to learn how to efficiently navigate this seemingly benign landscape that is actually hiding an obstacle course, pitfalls, natural mazes, and seabird burrows that can swallow your entire leg. Think of the miles here like you would dog years—one hike feels more like seven and can take just as long to complete. Since one of my roles is to navigate bird monitoring transects that span the entire island, and because daylight is limited at this latitude in the middle of winter, it is critical I quickly learn how to reduce my hiking time.

My first trip across Antipodes Island is with fellow biologist Sarah Forder. Our goal is to conduct a distance sampling of the island’s ground birds prior to our first operation to remove damaging invasive mice. We begin our journey with a ride to the distant south coast of the island in one of the three helicopters supporting the project. We land in an abandoned penguin colony 6.2 km (~3.8mi) from our camp (don’t forget the dog years!).

We plan to conduct four transect lines from south to north observing and documenting the three ground birds endemic to the Antipodes – Reischek’s Parakeet (Cyanoramphus hochstetteri), Antipodes Island Parakeet (Cyanoramphus unicolor) and the Antipodes Island Pipit (Anthus novaeseelandiae steindachneri). This monitoring baseline will help us measure the bird’s anticipated recovery and other responses to life on the island without invasive mice.

Our first transect line starts along the south coast where the vegetation is scattered in dense patches. I quickly find myself laboring uphill through the bush to complete my line. Thankfully, my effort is rewarded with a spectacular view of the pristine subantarctic landscape rarely seen by anyone other than the occasional intrepid researcher or facilities maintenance staff.

Side note: this particular site is actually the setting of an epic shipwreck story. Survivors from the Spirit of the Dawn, an iron barque (sailing vessel) weighing 716 tons, wrecked on the southwest coast of Antipodes Island in 1893. This story is well documented in the book Straight from London, by Rowley Taylor.

It’s approaching midday and we still have three more transect lines to complete before our 6km hike back across the island to camp. I start doubting myself. Will I get caught spending the night out here? Is a helicopter return trip even possible?

With a hint of fatigue barely masked by her kiwi accent, she delivers her sage advice with a smile, “No worries; Just keep going José!”

Given our daylight constraints (it gets dark at 4:30 pm), Sarah and I decide to conduct transect lines separately to save a bit of time. We split our tracks to cover the main western and eastern routes back across the island. Before you conjure up visions of well-established trails, bear in mind that down here the concept of “routes” is more symbolic as there are no established marked trails on the island. Antipodes Island is a designated Natural Reserve as well as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its outstanding universal value. To preserve the island’s unique natural systems, plants, and animals, biosecurity plans prevent public visitation to Antipodes Island. Hence, there are no trails.

Based on my prior experiences navigating the local terrain, and that the majority of my fieldwork has been in tropical locations with vastly different landscapes, I ask Sarah for any tips to more effectively navigate through the vegetation. With a hint of fatigue barely masked by her kiwi accent, she delivers her sage advice with a smile, “No worries; Just keep going José!”

With that in mind, I walk, scramble, and swim through very steep tussock grass and ferns. With every step, it feels like I am falling through gaps in tussock and ferns. It soon dawns on me that if I continue at my current pace, I will not arrive back to camp before dark. I need to put some distance between me and the south coast. I decide to switch my strategy and try to walk on the tops of the vegetation “islands”. But, I continue missing steps and plunging out of sight between the vegetation with frustrating regularity. These are not small falls, but rather full body disappearing acts. I am seriously beginning to wonder if this vegetation is truly conspiring against me.

I still have 5 km left to get to the Biodiversity Hut. I hear Sarah in my head, and I just keep going. I force myself to walk as fast as possible through the thick tussock and near impenetrable ferns. After a half-hour of difficult travel, I come across a small stream in the interior of the island that thankfully provides a much clearer route of travel. I finally start making decent progress toward my next transect! This transect is a godsend as it just about follows the contour of the stream and gives me much-needed relief from my previous bushwhacking. I complete my transect line, only to realize I still have 4.3 km left. For the second time I think,

I really might need a helicopter…or I could be staying the night out here…

Daylight is waning, so I decide I better save my last transect for another day (maybe I could convince Jason to do it!). Perhaps it is my mind growing weary or adrenaline flowing for fear of being trapped out here for the night in the darkness, but I soon find myself walking a little faster.

With a bit more grace and fewer falls, I encounter heroic near-misses that remind me of characters in The Matrix movies. I calculate that I still have 3.5 km left go.

I start coming to terms with the fact that I am probably going to be spending the night in the open subantarctic tussock country.

Fortunately, I do have a small waterproof survival bivy and a borrowed poncho liner, but these items do little to lighten my mood. I decide on a quick stop to eat and consider possible options to safely pass the night. I recall the story of the survivors from the Spirit of the Dawn and what they did to keep themselves as warm as possible at night.

After finishing my snack, I realize how exhausted I am and find myself growing more tired despite my boost in blood sugar. I send Sarah a satellite message and attempt to establish a radio contact at camp. No luck. There are only 30 minutes of light left. Given this, I decide I should try and find a little shelter from the elements. I start to secretly hope that the rest of the team will realize my situation and send a helicopter to come and get me. A dense blanket of fog begins to descend on the island. Suddenly, I hear Sarah’s words repeating over and over in my head… “Just keep going José”, like a mantra. No worries! I will keep pushing on! I will make it back – even if it is in the dark!

The vegetation in the middle of the island is composed of the same species previously mentioned, but with the welcome addition of more bryophytes and lower overall height of the tussocks and ferns – which creates more of a tundra landscape. The ground is easier to walk on and the ever-present uneven landscape gives you the feeling that you are advancing faster than ever. I find a small creek which I follow (again), until a giant muddy hole takes possession of one of my gumboots, leaving me with a soggy, exposed sock.

As I am trying to free my boot from the jaws of this tundra mud trap, I hear the radio crackle. It is radio communication from one of the helicopter pilots calling me for my location so I can get picked up!

One minute later, the helicopter broke through the mist, and like a magic dream, I am loaded up and whisked away to our little pocket of civilization. No worries, indeed!

Flying back to the camp, the vegetation sure doesn’t look so difficult to walk through, but we all know the reality is far different. Looking down from the air, I realize that I am closer to the hut than I thought, but, given the waning of daylight, I was never going to arrive before dark. The helicopter probably saved me a night out on the tundra.

Humbled by this landscape, my monitoring responsibilities continue. I am destined to return to the south coast of Antipodes Island in the near future to conduct more monitoring of endemic ground birds and again pit myself against the challenging landscape. I continue training myself every day in new techniques to improve travel through the vegetation and I will be better prepared for my next round of Antipodes trekking.

While I’m making steady progress, I still routinely find myself head over heels, swimming through tussock, clawing through ferns and swimming in sedge. It’d be easy to let frustration creep back in and dominate my mind like it did on my first south coast adventure. But, I find myself harkening back to Sarah’s encouraging words which I now apply to most tough situations I face here. “No worries; Just keep going José!”

Designated as a world center of floristic diversity, Antipodes Island currently has recorded 77 individual plant species: 73 natives including 5 endemic species and 4 exotic introduced species. The flora and fauna of Antipodes Island are worth all this effort…I just want them to all be able to have no worries and keep going!

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!

Three Island-Ocean Connection Challenge projects in the Republic of the Marshall Islands bring hope for low-lying coral atolls!

A new article in Caribbean Ornithology heralds the success of one of our most exciting restoration projects: Desecheo Island, Puerto Rico!

Part 2 of filmmaker Cece King's reflection on her time on Juan Fernandez Island in Chile, learning about conservation and community!

Read about Nathaniel Hanna Holloway's experience doing marine monitoring in the Galápagos!