New Paper Demonstrates Quality of eDNA Monitoring for Conservation

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

Our new online shop is live!

Published on

January 14, 2013

Written by

Heath

Photo credit

Heath

January 28, 2013

Joan Jewett, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 503-231-6211

Removing non-native rats was the top priority for the Palmyra Atoll Restoration Project, a multi-year effort to protect 10 nesting seabird species, migratory shorebirds, the rare coconut crab, and one of the largest remaining native Pisonia grandis forests (a rare flowering tree in the Bougainvillea family) in the tropical Pacific.

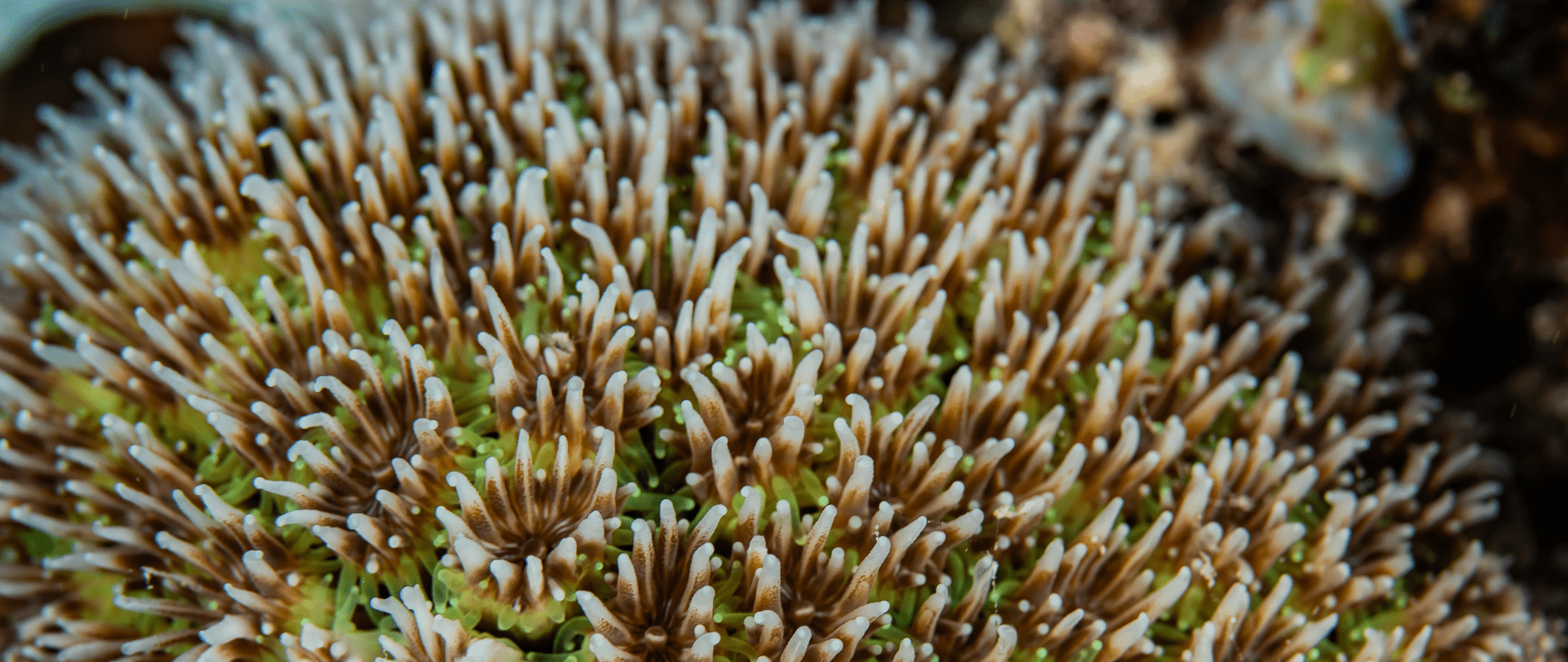

Palmyra Atoll, approximately 1,000 miles south of Honolulu, Hawai‘i, is cooperatively managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and The Nature Conservancy as a National Wildlife Refuge and a scientific research station. The area includes 25 islets covering 580 acres of land, and thousands of acres of healthy coral reefs. In 2009, the refuge and waters surrounding it were also included in the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument.

Non-native black rats were likely introduced to the atoll during World War II, and the population grew to as many 30,000 rats. The invasive rodents eat eggs and chicks of ground and tree-nesting birds, particularly sooty and white terns. Rats also eat land crabs and the seeds and seedlings of native tree species.

Using the same proven methods that were used years before to detect the extent of the rat problem on Palmyra, scientists conducted surveys over a month-long period this summer and confirmed that the entire atoll is currently rat-free. In the tropical climate at Palmyra, rats reproduce approximately once every 3-4 months, so conducting surveys one year after the removal effort is sufficient time to detect rats remaining on the atoll. During the summer, the project partners established a network of 286 rat detection stations that covered the entire atoll. Each station was checked four times during the course of one month. Aside from the detection stations, team members spent hundreds of hours scouring the atoll for natural indicators of rat presence. In accordance with observations of the recovery of native species over the past year that suggested that the project was successful, the recent monitoring found no rats after one year.

“Millions of seabirds, trees, crabs and other native species can now thrive in their home without the threat of being eaten by rats. Staff and visitors to the atoll have seen a large increase in the numbers of crabs, insects, seedlings and seabirds. Our collective efforts to bring balance back to Palmyra are working. The scientific rigor, attention to detail, and collaboration is a testament to the integrity and cooperative nature of our partnership,” said Suzanne Case, Executive Director of The Nature Conservancy’s Hawai’i program.

The University of California Santa Cruz Coastal Conservation Action Lab (UCSC-CCAL) is monitoring the response of Palmyra’s terrestrial ecosystem by comparing measures of seabird, shorebird, and plant populations taken before and after rat removal. In the summer of 2012 they found dramatic increases, including:

· Over 130% increase in native tree seedlings (Palmyra has ten locally rare native tree species), and the first record of Pisonia seedlings (no seedlings were observed in 2007 prior to rat removal);

· A 367% increase in arthropods (such as insects, spiders, and crabs); and

· No change in Bristle-thighed Curlews found at Palmyra (special care was taken to ensure this imperiled species was not negatively impacted by the rat removal project)

“With the atoll free of rats, we are already seeing a dramatic increase in many things that rats preyed upon: nesting seabirds, migratory shorebirds, native tree seedlings, and small invertebrates like fiddler crabs. The island is truly rebounding,” said Gregg Howald, North America Regional Director, Island Conservation.

Although Palmyra is rat-free today, the threat of re-introducing rats or other invasive species is present anytime a boat or airplane travels to the atoll. A detailed prevention plan is in place to minimize the threat of non-native species being introduced to the atoll.

The removal of introduced species such as black rats is a proven, effective conservation tool that has been successful on numerous islands across the globe, including the Galapagos archipelago, a multitude of islands in New Zealand, the Channel Islands off the coast of California, and Hawadax Island (formerly ‘Rat Island’) of the Aleutian Island chain in the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge.

Additional Resources Available:

You can download a copy of this press release here

Check out other journal entries we think you might be interested in.

Groundbreaking research has the potential to transform the way we monitor invasive species on islands!

Ann Singeo, founder of our partner organization the Ebiil Society, shares her vision for a thriving Palau and a flourishing world of indigenous science!

This historic agreement aims to protect the marine and coastal areas of the Southeast Pacific.

Our projects to restore key islets in Nukufetau Atoll forecast climate resilience and community benefits in Tuvalu!

Endangered Polynesian storm-petrels returning to Kamaka Island, French Polynesia within one month of social attraction tools being deployed. Polynesian storm-petrels have not been recorded on Kamaka Island for over 100 years due to invasive rats. These seabirds are able…

Our new branding and website support our vision of a world filled with vibrant biodiversity, resilient oceans, and thriving island communities!

Audubon's Shearwaters are nesting on Desecheo Island for the first time ever! Read about how we used social attraction to bring them home.

Island Conservation and partners have published a new paper quantifying ecosystem resilience on restored islands!

Climate Week NYC: what is it and why is it important? Read on to find out why Island Conservation is attending this amazing event!

With sea levels on the rise, how are the coastlines of islands transforming? Read on to find out how dynamic islands really are!